Pain and Profit in Sovereign Debt: How New York Can Stop Vulture Funds from Preying on Countries

December 2021

Org Blurbs

The Center for Popular Democracy is a nonprofit organization that promotes equity, opportunity, and a dynamic democracy in partnership with innovative base-building organizations, organizing networks and alliances, and progressive unions across the country. www.populardemocracy.org

The Center for Popular Democracy is a nonprofit organization that promotes equity, opportunity, and a dynamic democracy in partnership with innovative base-building organizations, organizing networks and alliances, and progressive unions across the country. www.populardemocracy.org

Churches United for Fair Housing CUFFH is a grassroots organization that works towards community empowerment through community organizing, youth engagement and by providing sophisticated social services. CUFFH organizes towards preserving and creating vibrant communities that are not exclusive and are really affordable to working families in New York City. https://www.cuffh.org/

Churches United for Fair Housing CUFFH is a grassroots organization that works towards community empowerment through community organizing, youth engagement and by providing sophisticated social services. CUFFH organizes towards preserving and creating vibrant communities that are not exclusive and are really affordable to working families in New York City. https://www.cuffh.org/

The Hedge Clippers are working to expose the mechanisms hedge funds and billionaires use to influence government and politics in order to expand their wealth, influence and power. We’re exposing the collateral damage billionaire-driven politics inflicts on our communities, our climate, our economy and our democracy. We’re calling out the politicians that do the dirty work billionaires demand, and we’re calling on all Americans to stand up for a government and an economy that works for all of us, not just the wealthy and well-connected. https://hedgeclippers.org/about

The Hedge Clippers are working to expose the mechanisms hedge funds and billionaires use to influence government and politics in order to expand their wealth, influence and power. We’re exposing the collateral damage billionaire-driven politics inflicts on our communities, our climate, our economy and our democracy. We’re calling out the politicians that do the dirty work billionaires demand, and we’re calling on all Americans to stand up for a government and an economy that works for all of us, not just the wealthy and well-connected. https://hedgeclippers.org/about

LittleSis is a grassroots watchdog network connecting the dots between the world’s most powerful people and organizations. We bring transparency to influential social networks by tracking the key relationships of politicians, business leaders, lobbyists, financiers, and their affiliated institutions. https://littlesis.org/

LittleSis is a grassroots watchdog network connecting the dots between the world’s most powerful people and organizations. We bring transparency to influential social networks by tracking the key relationships of politicians, business leaders, lobbyists, financiers, and their affiliated institutions. https://littlesis.org/

New York Communities for Change is one of the largest grassroots, membership-driven, community-based organizations in New York. NYCC uses community organizing, direct action and legislative advocacy to advance the cause of social and economic justice in low and moderate income communities. https://www.nycommunities.org/

New York Communities for Change is one of the largest grassroots, membership-driven, community-based organizations in New York. NYCC uses community organizing, direct action and legislative advocacy to advance the cause of social and economic justice in low and moderate income communities. https://www.nycommunities.org/

Executive Summary

Vulture funds have spent decades honing a predatory playbook designed to extract maximum profits out of struggling, debt-ridden countries. The vulture fund business model involves buying up heavily discounted debt from countries in financial trouble, refusing to engage in good faith negotiations to cut debt obligations by a reasonable amount, and then suing the country to demand full repayment. Vulture funds have made exorbitant profits deploying this playbook, which often involves freeriding on the money a country accumulates through development aid and the implementation of austerity measures. This report profiles notorious billionaire vulture investors like Paul Singer and Kenneth Dart who have perfected this playbook, and highlights real world examples of their predation in action, from Argentina to the Republic of Congo.

In the past few decades, New York State law has played a key role in enabling the vulture fund playbook. In the absence of a binding international sovereign debt restructuring framework, vulture funds have weaponized New York law in their quest to extract as much money as possible from struggling countries. Because most sovereign debt contracts are governed by either New York State or English law, New York is uniquely positioned to step in and pass laws that would disrupt the vulture fund playbook and stop them from profiteering at the expense of countries in financial trouble. Specifically, New York lawmakers can take immediate action by providing a framework for restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt; barring the purchase of sovereign debt for the purpose of filing a lawsuit; and eliminating one of the vulture funds’ favorite tax loopholes which allows investment managers’ fees to be taxed at a far lower rate than workers’ wages.

Introduction

In recent decades, Wall Street investors seeking short-term gains have amassed enormous amounts of sovereign debt—debt issued by governments—owed by countries in financial distress.

Called “vulture funds,” these predatory investors buy up debts owed by struggling governments, demanding to be repaid at face value. These unscrupulous investors then use their financial position to profit from austerity measures imposed on the countries they target. Vulture funds extract debt payments to enrich themselves while communities face regressive taxes, slashed public services, and privatized public goods.

Billionaire Paul Singer is one of the most notorious examples of a vulture investor who has made exorbitant profits using this predatory and exploitative business model. Singer’s hedge fund Elliott Management has gone to unbelievable lengths to squeeze struggling countries for debt payments.

Singer was the mastermind behind a 15-year fight to extract $2.4 billion from the government of Argentina for bonds that the fund had purchased for $117 million.[1] In pursuit of a maximum payout on this debt investment, Elliott Management famously spurred an international incident when it arranged for the government of Ghana to seize an Argentine naval ship and impound it for collection on behalf of his hedge fund.[2]

While Elliott Management’s successful vulture attack on Argentina is famous for its brazenness, it is far from the only example of vulture funds preying on countries in economic crisis.

Vulture funds have followed a well-established playbook, which includes:

- Buying sovereign debt at a steep discount;

- Holding out during debt negotiations to block any restructuring deals;

- Initiating protracted lawsuits to drain countries’ resources and further stymie efforts to restructure debts;

- Taking advantage of austerity measures and international debt relief initiatives; and

- Maximizing payouts at the expense of local communities.

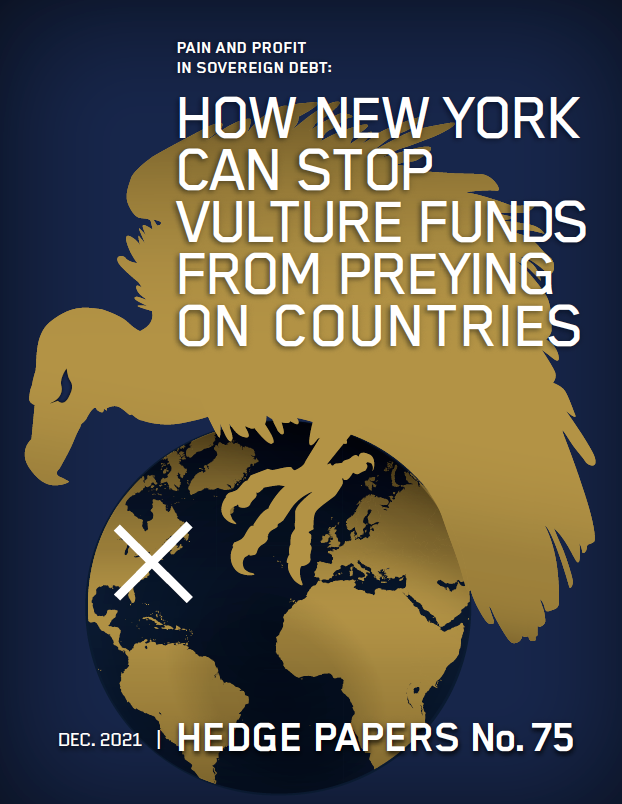

Vulture funds have run this scam across the world, targeting countries like Argentina, Greece, Peru, and the Republic of Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville), as well as Puerto Rico. Their playbook also relies heavily on favorable legal judgments from federal courts in New York because the majority of sovereign debt contracts around the world are governed by New York State or English law.[3]

This report details the vulture fund playbook and the role of New York State law in enabling this system of exploitation. Using concrete examples from around the world, we demonstrate how vulture funds have amassed incredible wealth by utilizing New York State law to extract maximum payouts from struggling, debt-ridden countries.

We also provide specific policy recommendations for New York lawmakers who want to disrupt this playbook and stop vulture funds from profiteering at the expense of vulnerable countries. New York law should be changed to:

- Provide a framework for restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt to stop holdout vulture investors from blocking debt restructuring deals;

- Bar the purchase of sovereign debt for the purpose of filing a lawsuit by strengthening New York’s “champerty” law; and

- Eliminate one of the vulture funds’ favorite tax loopholes, which allows investment managers’ fees to be taxed at a far lower rate than workers’ wages.

Vulture funds’ relentless pursuit of profit has left unimaginable devastation in its wake, hurting millions of people who live in struggling countries and jeopardizing these countries’ long-term economic well-being. Because of New York’s position as the world’s financial capital, and its unique role in governing sovereign debt contracts globally, lawmakers in the state must take action to disrupt the vulture fund playbook and end this predatory behavior.

Vulture Funds’ Predatory Sovereign Debt Playbook

Vulture funds have spent decades honing a predatory playbook designed to extract maximum profits out of struggling, debt-ridden countries.

The vulture fund business model involves buying up heavily discounted debt from countries in financial trouble, refusing to engage in good faith negotiations to cut debt obligations by a reasonable amount, and then suing the country to demand full repayment.

Vulture funds have made exorbitant profits deploying this playbook, which often involves free-riding on the money that governments accumulate through the implementation of austerity measures, as well as debt relief and development aid that is intended to support struggling countries.[4]

While vulture funds cash in, good faith creditors who are actually participating in the debt restructuring process end up getting less. Vulture funds hold other creditors and debtor countries hostage, which results in a volatile and inefficient debt restructuring system.[5]

Vulture funds’ relentless pursuit of profits jeopardizes the long-term economic well-being of the countries they target while hurting millions of struggling people.

Step 1: Buy sovereign debt at a steep discount

Vulture funds start by buying up a country’s debt, often swooping in when the country is at its most vulnerable. They buy heavily discounted and distressed debt when a country is in financial trouble, often when it has already defaulted on its debt, when a default is likely, or after a natural disaster.[6] Their business model explicitly takes advantage of rock bottom prices and financial instability to buy a stake in a country’s debt.

The vulture playbook in practice:

- Elliott Capital, led by notorious billionaire Paul Singer, snatched up Argentinian bonds for pennies on the dollar after the country defaulted on over $100 billion in debt in 2001.[7] Years prior, in 1996, Elliott Capital began to accumulate Peru’s debt after it had defaulted and already reached a broad-strokes agreement with its creditors to cut their debt obligations.[8] That same year, a subsidiary of Elliott Management began buying old debt worth $30 million owed by the Republic of Congo, eventually winning judgments in a UK court which awarded them more than $121 million.[9]

- When billionaire vulture fund manager Kenneth Dart bought up Brazilian sovereign debt in the early 1990s, he paid a mere $375 million for debt worth $1.4 billion. This move enabled Dart to become Brazil’s largest private creditor in the process, eventually owning 4% of the country’s external debt.[10]

- In 2014, Puerto Rico’s debt ratings were downgraded and the island lost access to capital markets.[11] That same year, around 60 hedge funds held $16 billion (approximately 22%) of Puerto Rico’s debt.[12]

- Mark Brodsky, chairman of the hedge fund Aurelius Capital Management, started buying Puerto Rican bonds in 2015—the year the then-governor of Puerto Rico declared the debt unpayable. Brodsky is a hedge fund manager who has made his fortune using the vulture fund playbook.[13]

- After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017, several hedge funds took advantage of low prices to significantly increase the amount of Puerto Rican debt they owned. For example, hedge fund GoldenTree Asset Management increased their Puerto Rican bond holdings from $587 million the month before Maria to $1.5 billion a year later.[14]

Step 2: Hold out during debt negotiations to block any restructuring deals

Step 2: Hold out during debt negotiations to block any restructuring deals

When countries are facing financial distress or defaults on their debts, they must negotiate directly with creditors. This is because, in contrast to individuals and corporations that file for bankruptcy in the United States, countries do not benefit from legally binding bankruptcy protections. None exist under international or domestic law. While creditors can choose to negotiate, there is nothing compelling them to cooperate in good faith during debt restructurings.[15]

As a result of this loophole in the law, a favorite vulture fund tactic is to “hold out” during debt negotiations, even when they own a small percentage of a country’s debt and the rest of the creditors are willing to negotiate in good faith. By refusing to negotiate—or to accept any proposed debt restructuring agreements—vulture funds can disrupt the process for all creditors while preventing a country from accessing international capital markets.[16]

This hold out tactic hurts struggling countries in several key ways:

- It drags out the debt restructuring process, making it more protracted, volatile, and expensive for all parties involved;

- It drains the money and resources a country can devote to financial recovery by 1) reducing the positive impact of debt relief the country receives, and 2) ensuring that taxes designed for debt relief are reallocated to vulture funds; and

- Ultimately, vulture funds cash in while creditors who are participating in the restructuring get less. Vulture funds, in effect, are freeriders who hold both other creditors and the debtor country hostage.[17]

The current lack of a sovereign debt restructuring framework incentivizes vulture funds to exert enormous leverage by choosing to hold out for full repayment rather than cooperate with the country facing default. In turn, countries in economic distress are at the whim of predatory creditors.[18]

The vulture playbook in practice:

- In the case of Peru, out of approximately 180 creditors, only Elliott Capital and Pravin Banker refused to participate in a negotiated restructuring agreement.[19]

- During negotiations with Argentina, Elliott Capital and other hedge funds refused the proposed restructuring deal—even though 93% of the country’s creditors were prepared to sign. This coercive and unilateral approach to debt restructuring, set a toxic precedent for future debt negotiations around the world. Argentina’s 2001 default affected nearly half a million creditors while just a handful of vulture funds held those creditors hostage.[20]

- When the Republic of Ecuador sought to restructure $17.4 billion in sovereign debt in July 2020, it reached a deal with a committee representing owners of a majority of its bonds.[21] A hold-out group representing owners of a minority of bonds opposed the deal.[22] Two members of the steering committee representing these minority bondholders—hedge funds Contrarian Capital and GMO Trust—went on to sue Ecuador in the Southern District of New York to try to block the deal.[23]

- In 1984, Puerto Rico was written out of Chapter 9 of the US Bankruptcy Code, which governs municipal bankruptcies.[24] This meant that, like sovereign countries, Puerto Rico (a US colony) had no mechanism to force creditors to the negotiating table.

- Vulture funds fought hard to maintain this status quo, which would enable them to hold out. For example, hedge fund BlueMountain Capital Management spent $100,000 on Washington DC lobbyists in just the first quarter of 2015, all to prevent Puerto Rico from gaining bankruptcy protections. They also sued to invalidate a Puerto Rico law that sought to provide bankruptcy protections to public corporations.[25]

Step 3: Initiate protracted lawsuits to drain countries’ resources and further stymie efforts to restructure debts

After buying a county’s distressed debt and refusing to negotiate, vulture funds then use high-powered lawyers to take countries to court, all in an attempt to grind them down in endless cycles of litigation.

Vulture funds sue to get an order from a judge mandating the indebted country pay them in full, and then continue using the courts to try to get paid by any means possible. This prevents debt restructuring processes from progressing and proves enormously expensive to already debt-strapped countries.[26] These legal battles can go on for years—often 3 to 10 years—before a settlement is reached.[27]

Vulture funds make up the majority of the creditors bringing lawsuits in debt repayment scenarios.[28]

Even as the number of debt restructurings went down from the 1980’s to the 1990’s, since the mid-90’s to today, an increasing number now involve legal battles with vulture funds.[29] In fact, only 5% of debt restructurings involved lawsuits in the 1980’s. By the year 2000, an estimated 50% involved lawsuits. Vulture funds led the majority of these lawsuits against highly indebted African and Latin American countries.[30]

Between 1976 and 2010, foreign creditors filed over 150 lawsuits against 34 countries in default. These disputes often end up in courts in New York because many countries’ sovereign debt contracts are governed by New York law. In fact, over 80% of the cases filed from 1976 to 2010 were in courts in New York.[31]

The vulture playbook in practice:

The vulture playbook in practice:

- In many respects, billionaire Paul Singer wrote the vulture fund playbook. He became the first creditor to go after a sovereign nation for debt in a US court in the 1990’s when he successfully sued Panama.[32] Since then, he has specialized in aggressive and drawn-out sovereign debt litigation while inspiring other vulture funds to follow suit.[33]

- Singer notoriously spent 15 years battling Argentina over bond debt that eventually reached the US Supreme Court. This was in addition to Singer’s legal battles with Peru, Vietnam, the Republic of Congo, and more.[34] Singer employs a range of ruthless legal tactics, like his attempt to seize and freeze Argentina’s assets.[35] His vulture fund wasn’t just seeking to recoup its initial investment, it was demanding enormous profits and years of accrued interest.[36]

- Singer, along with the other holdouts in Argentina’s debt restructuring, brought 11 lawsuits in federal courts in New York and won every single one. A judge in the Southern District of New York went so far as to prohibit Argentina from paying any creditors who agreed to the deal unless the vulture funds were paid in full at a cost of $4.65 billion to Argentina.[37]

- In 1999, through the Peru sovereign debt litigation, Paul Singer had cleared a legal obstacle to his playbook. Peru had challenged Elliott Management’s demand for full repayment by arguing that the vulture fund had violated New York’s champerty law, which seeks to prohibit predatory financial actors from buying financial instruments for the primary purpose of filing a lawsuit.[38] Although the judge initially ruled in favor of Peru, Singer won on appeal.[39]

- Singer did not stop there. Following intense lobbying efforts by Elliott Capital, the New York state legislature created a loophole that exempts debt transactions of over $500,000 from the law’s grasp, “ensur[ing] the good health of the vultures’ business.”[40]

- Contrarian Capital and GMO Trust sued Ecuador in the Southern District of New York in July 2020 trying to block a debt restructuring deal made with a group representing owners of a majority of Ecuador’s government bonds.[41] This suit was dismissed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in August 2020.

- GMO Trust also sued Ecuador in 2014 over the country’s 2008 default on sovereign debt, eventually dropping the suit after reaching a settlement with Ecuador’s government.[42]

- Elliott Management subsidiary Kensington International waged a years-long litigation campaign against the Republic of Congo over debts the nation incurred in the 1980s. Kensington bought the debt starting in 1996 and began suing the country, then in the midst of a civil war. By August 2005, Kensington had won awards in UK courts worth more than $121 million. Then Kensington “launched the most aggressive phase of its recovery effort,” seeking to seize Congolese assets and suing companies connected to Congolese government officials around the world, including in New York, as well as other creditors to the Republic of Congo like French bank BNP Paribas.[43] Kensigton’s campaign included leaking information about government corruption to global NGOs. The Republic of Congo eventually settled with Kensington, “for an undisclosed amount,” in 2007.[44]

- In the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo (also called Congo-Kinshasa), the New York-based FG Capital Management took the DRC to court and attempted to seize the country’s assets in the Bahamas, Europe, South Africa, the US, and Hong Kong. FG Capital successfully got a US court to hold the DRC in contempt of court for refusing to disclose assets.[45] This legal action took place between 2008–2009, a time when the country was dealing with widespread civil conflict and instability.[46]

- In Puerto Rico this step of the playbook unfolded differently because, in 2016, the US Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which provided bankruptcy protections. (It is important to note, however, that these bankruptcy protections came at the cost of the creation of a board that has used its power to impose austerity measures and negotiate unsustainable debt restructuring plans.) Nonetheless, vulture funds did resort to protracted litigation battles and co-opted the bankruptcy court proceedings to their benefit.

- For example, hedge fund Aurelius Capital, which had just 0.5% of Puerto Rico’s debt at the time, took a legal challenge of a key aspect of PROMESA all the way to the US Supreme Court in an attempt to jeopardize the leverage Puerto Rico had gained in debt restructuring negotiations.[47] Their attempt was unsuccessful.

- However, hedge funds have been able to co-opt the bankruptcy court proceedings to their benefit in a way similar to the way they have co-opted bankruptcies under Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code (governing corporate bankruptcies), including by acquiring a stake large enough to gain some control over the restructuring process, holding positions on creditors’ committees, and leveraging their bankruptcy expertise.[48] The Puerto Rico Financial and Oversight Management Board, an unelected and unaccountable body created by PROMESA, has been complicit in this co-optation. The Board has enabled hedge funds to exert undue control over the process and has largely turned a blind eye to allegations of wrongdoing that could get in the way of hedge fund profits.[49]

Only 5% of debt restructurings involved lawsuits in the 1980’s. By the year 2000, an estimated 50% involved lawsuits. Vulture funds led the majority of these lawsuits against highly indebted African and Latin American countries.[50]

“Doomsday Investor:” Notorious Billionaire Paul Singer of Elliott Capital has amassed billions while developing nations suffer “Doomsday Investor:” Notorious Billionaire Paul Singer of Elliott Capital has amassed billions while developing nations suffer

Paul Singer, founder of the $45 billion vulture fund Elliott Capital, has a reputation for predatory and combative approach to dealmaking.[51] Singer has been termed a “Doomsday Investor” in the press and has employed outrageous tactics to get a payout during his frequent sovereign debt deals.[52] During his notorious 15-year battle with Argentina over its debt, Paul Singer:

The government of Argentina had to waste enormous legal resources to respond to each of Singer’s outrageous stunts, which enraged the people of Argentina.[56] Elliott Management was highly litigious and pursued Argentina in the courts and even took a claim to the US Supreme Court.[57] His fund relied on slippery legal arguments to force sovereign nations to pay vulture funds before being able to pay other creditors, and his vulture fund consistently prevailed in New York courts.[58] All of these unscrupulous tactics resulted in a $2.4 billion payout from Argentina to Singer’s firm in 2016, a 1,270-per-cent return on its initial investment.[59] Singer chairs the anti-union, climate science-denying Manhattan Institute and has been termed a “passionate defender of the 1%.”[60] Singer, who reportedly played piano in an all-white reggae band,[61] spends his off time in luxury apartments in Manhattan or one of his two $9 million ski chalets in Aspen, Colorado.[62] Singer’s relentless and ruthless efforts have enabled him to amass a $4.3 billion fortune.[63] |

Step 4: Taking advantage of austerity measures and international debt relief initiatives

Protracted legal battles with vulture funds prevent debt restructurings from progressing and are a significant drain on a country’s resources. When countries are caught in limbo with unsustainable debt burdens, over time they can lose access to credit markets, which leaves them unable to meet even the basic needs of their population.[64] As countries’ legal fees mount, they are often unable to fully fund vital services.

By one estimate, vulture fund lawsuits cost these countries the equivalent of 18% of their spending on healthcare and education alone.[65]

When the World Bank or international bodies step in with funding, vulture funds often prey on the debt relief that these struggling countries receive. According to the World Bank, vulture funds have targeted more than one-third of “highly indebted poor countries” that qualified for relief, securing legal judgments totaling a staggering $1 billion. In the process, they free-ride on this debt relief (which is designed to alleviate poverty) and effectively turn international humanitarian relief into corporate profits.[66]

Vulture funds both benefit from austerity imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) through conditional lending and help to drive austerity policies in their pursuit of profit as resources for social spending are diverted to debt repayment

Often, the IMF and other international financial institutions condition loans and other resources on “extensive domestic policy reforms, including opening to international trade and finance; privatizing natural resources and state-owned enterprises; deregulating economic activities; reforming the provision of social services; and a range of market-oriented institutional reforms.”[67]

These reforms often translate to profit-friendly policies for wealthy investors, including vulture funds, and austerity for low-income residents of indebted countries.

The vulture playbook in practice:

- Up until 2017, the Venezuelan government failed to provide basic food and medicine to its residents while still continuing to pay back bond payments in full. The government prioritized bondholders over its people for fear of legal risks and the threat of litigation.[68] As far back as 1989, the Venezuelan government was reportedly imposing austerity at the urging of its creditors which sparked public outcry and uprisings that turned deadly for over 300 protesters that year.[69]

- In July 2020, the group of investors owning a majority of Ecuador’s sovereign debt conditioned their acceptance of a debt restructuring deal on the country receiving aid from the IMF. According to the Financial Times: “The IMF agreement played an instrumental role: The deal with bondholders was contingent on it. If the IMF had not agreed to a lending programme by the September 1 deadline, the whole restructuring plan could have fallen apart.”[70] The IMF’s aid in turn was conditioned on Ecuador acceding to “adopting robust cash management practices, improving transparency in public procurement, and promoting debt transparency.”[71]

- Ecuador had seen mass anti-austerity protests the previous year in 2019, after then-President Lenín Moreno signed an agreement with the IMF that February which “benefited multinational corporations, the banks, and in general, powerful economic groups at the expense of the middle and working classes.”[72]

- In September 2021, Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso announced his intent to “cut [Ecuador’s] fiscal deficit in half to around $2.4 billion in 2022 through austerity measures such as layoffs of state workers.”[73]

- In 1990, the president of Peru announced austerity measures including the elimination of all government subsidies of consumer goods and increases in the price of food and utilities. The price of gasoline increased thirtyfold and the price of bread and milk nearly tripled.[74] Following the announcement, at least three people were killed by troops deployed to the streets in anticipation of looting.[75] As people in Peru were contending with crushing austerity, New York courts forced Peru to pay vulture fund Elliott Capital the original value of its bonds and almost sixty million dollars in interest.[76]

- In Puerto Rico, the unelected and unaccountable Financial Oversight and Management Board created by federal law in 2016 has final say in the island’s fiscal plans and budgets.[77] That means the Board has immense power to impose austerity measures to set aside billions of dollars for debt repayment.

- The Board has called for rate increases for tolls, water, and electricity—even though local customers pay almost twice as much as customers in the US; weakening labor protections for workers; massive cuts in education funding, including hundreds of school closures and tuition hikes; pension cuts to current and future retirees; significant cuts to healthcare; cuts to funding for local municipalities; and narrowing eligibility for the Nutritional Assistance Program.[78]

- Additionally, the Board used the money Congress appropriated for Hurricane Maria relief efforts to justify increased payouts to vulture funds.[79]

| In 2014, the United Nations Human Rights Council formally condemned vulture funds “because they (1) paralyze debt restructuring efforts of developing countries; (2) frustrate the sovereign state’s right to protect its citizens under international law; (3) increase the debt burden of extreme poverty countries; and (4) diminish the impact of debt relief.”[80] |

Step 5: Maximize payouts at the expense of local communities

This vulture fund playbook—swooping in to buy distressed debt at bargain prices, holding out during debt restructurings, and taking countries to court—has proven wildly successful for both the funds and their investors.

Under current New York law, courts almost always side with vulture funds.[81] Given the complacency of the courts on these issues, the vulture fund playbook culminates in these funds securing staggeringly high rates of return on their initial investments at the expense of struggling countries and local communities. The result: vulture funds often average a rate of return 300–2000% on their initial purchase of distressed sovereign debt.[82]

The vulture playbook in practice:

- In the case of Argentina, Paul Singer’s unscrupulous tactics resulted in a $2.4 billion payout to his firm in 2016, a 1270% return on its initial investment.[83] Elliott Capital wasn’t the only vulture fund to walk away with billions: Bracebridge Capital, which purchased $120 million in bonds, eventually received $1.1 billion, while Aurelius managed to get $759 million for the $299 million in bonds it originally purchased.[84] This settlement happened in a year in which more than one in five Argentines lived in poverty.[85]

- Kenneth Dart, another vulture fund manager, has profited off sovereign debt in Greece, Brazil, and Argentina, among others.[86] After refusing to negotiate with Brazil during debt negotiations, Dart litigated in courts in New York and eventually got a favorable judgement in 1994. During an out-of-court settlement, Brazil was compelled to pay Dart accumulated interest, and the vulture fund was able to sell its Brazilian debt at an estimated 161% profit.[87]

- A handful of vulture funds made an estimated $1 billion in profits through the restructuring deal of Puerto Rico’s sales tax-backed COFINA bonds while the island was still reeling from the devastating effects of Hurricane Maria.[88]

Vulture fund billionaire Kenneth Dart, heir to the Dart foam-cups empire, is another controversial sovereign debt profiteer.[89] Vulture fund billionaire Kenneth Dart, heir to the Dart foam-cups empire, is another controversial sovereign debt profiteer.[89]

Kenneth Dart has amassed enormous profits in the sovereign debt world, buying up heavily discounted debt of financially distressed countries, refusing to participate in debt negotiations, and successfully securing profits through favorable judgements in the New York courts. Dart has profited off debt from countries like Greece, Argentina, and Brazil, to name a few.[90] The American-born billionaire renounced his US citizenship in the nineties and moved to a Cayman Islands tax haven.[91] In the Cayman Islands, some locals have likened him to a Bond villain. He lives in a former beachfront hotel formerly known as the West Indian Club. He is believed to own more Cayman Islands land than any one investor,[92] and has bought up land in Turks and Caicos, the Bahamas, and at least 10 other countries worldwide. Dart reportedly owns a 200-foot luxury yacht that is armored to withstand torpedo fire—reportedly to protect him from enemies amassed throughout years of predatory dealmaking.[93] Dart is notoriously secretive (his last interview was in 1993).[94] According to the Bloomberg Billionaire Index, Kenneth Dart’s net worth is $6.45 billion.[95] |

Policy Recommendations: New York State Must Act Now

Most sovereign debt contracts are governed by either New York or English law.[96] This means that New York is uniquely positioned to step in and disrupt the predatory playbook that has allowed vulture funds to profiteer at the expense of countries in financial trouble.

In the past few decades, New York law has played a key role in enabling the vulture fund playbook. In the absence of a uniform and binding international sovereign debt restructuring framework, vulture funds have weaponized New York law in their quest to extract as much wealth as possible from struggling countries. New York can act to stop this practice and change course by passing laws that would disrupt the vulture fund playbook.

- Provide a Framework for Restructuring Unsustainable Sovereign and Subnational Debt

New York must pass a law to provide a framework for countries to restructure their unsustainable debt.

This framework would create a process where an indebted government could restructure its debt by reaching an agreement with most of its creditors, without being held hostage by a small minority of creditors. If the requisite number of creditors agree to the terms of a debt restructuring agreement, they could bind a minority of dissenting vulture fund creditors to the agreed terms.

This framework would disincentivize vulture funds from holding out on debt restructuring negotiations.[97]

During the last New York State legislative session, both the Senate[98] and the Assembly[99] introduced legislation that would create this framework. Both chambers are expected to reintroduce the bill during the 2022 legislative session.

- Bar the Purchase of Sovereign Debt for the Purpose of Filing a Lawsuit by Strengthening New York’s “Champerty” Law

New York should strengthen its champerty law, which is intended to prevent predatory financial actors from buying financial instruments for the purpose of filing a lawsuit.[100] In theory, this should mean that vulture funds are prohibited from buying the debt of struggling countries at a steep discount just to weaponize New York law to demand full repayment (and reap sky-high profits).

In practice, two important developments have unfortunately gotten in the way of the intended effect of existing law:

- First, a Court of Appeals decision gutted its intended impact by finding that a vulture fund did not violate the champerty law because filing a lawsuit was not the sole purpose of buying the discounted debt—filing a lawsuit was contingent on not being paid in full.[101] However, the vulture fund could not have reasonably expected a country to pay them in full once it had already defaulted on its debt, unless it was forced to do so by a court.[102]

- Second, following intense lobbying efforts by Elliott Capital, the New York state legislature created a loophole that exempts debt transactions of over $500,000 from the law’s grasp.[103]

New York should strengthen its champerty law and make clear that it is unlawful for vulture funds to use New York law to profiteer from the distressed debt of struggling countries.

Additionally, the $500,000 loophole should be eliminated so that debt transactions of any amount are covered by the law.

- Eliminate One of the Vulture Funds’ Favorite Tax Loopholes

In addition to engaging in predatory practices, vulture funds and their investors do not pay their fair share of taxes. Hedge fund managers are compensated in two ways: a fee defined by a percentage of the money being managed (usually 2%), and a percentage of the returns they obtain from investing their clients’ money (usually 20%).[104] The vast majority of their profits are obtained through the latter arrangement, but since the returns are considered capital gains, they are taxed at a much lower rate than wages.

In New York, both the Senate and the Assembly have introduced bills that would address this inequity. One bill would zero in on the 20% of returns that hedge fund managers pocket, taxing them as the wages they are;[105] the other would tax all capital gains as wages.[106]

| New York State should use all the tools at its disposal to disrupt the vulture fund playbook and hold these predatory actors accountable. |

Which jurisdictions stand to benefit from these policy solutions?

The policy recommendations outlined in this report are poised to positively impact many countries around the world that have suffered at the hands of vulture funds.

Countries with sovereign debt contracts governed by New York law will benefit from these strengthened policy protections. Given that around half the world’s sovereign debt is governed by New York law, this would help millions of people in dozens of countries.[107]

Any country with sovereign debt contracts governed by any law other than New York law—most commonly English law—would not be covered, unless policymakers in those jurisdictions adopt similar policy reforms in tandem.

Unfortunately, because of Puerto Rico’s colonial status, its debt restructuring negotiations are controlled by US federal law. However, the recommended changes to New York law can help countries around the world avoid being held captive by vulture funds, and Puerto Rico could stand to benefit from it in the future once it is no longer a colony.

What’s at Stake

Vulture funds’ rapid expansion into sovereign debt has enabled them to extract maximum profits out of struggling, debt-ridden countries. Their relentless pursuit of profit has not only jeopardized the long-term economic well-being of the countries they target, it’s hurt millions of struggling people. Unfortunately, New York laws and courts have only enabled this predation, often siding with vulture funds in court and watering down the power of laws already on the books. Now New York can take a stand and ensure our state’s laws hold predatory vulture funds accountable. Specifically, New York lawmakers can take immediate action by adopting the policy recommendations in this report: providing a framework for restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt, barring the purchase of sovereign debt for the purpose of filing a lawsuit, and eliminating one of the vulture funds’ favorite tax loopholes that allows investment managers’ fees to be taxed at a far lower rate than workers’ wages.

Press and General Contacts

Julio López Varona jlopez@populardemocracy.org

Center for Popular Democracy

He/him

Jesus Gonzalez jgonzalez@populardemocracy.org

Center for Popular Democracy

He/him

Alicé Nascimento, ANascimento@nycommunities.org

New York Communities for Change

She/her

José González, jgonzalez@nycommunities.org

New York Communities for Change

He/him

Michael Kink mkink@populardemocracy.org

Strong Economy For All Coalition/Hedge Clippers/Center for Popular Democracy

He/him

Whitney Hu whu@cuffh.org

Churches United for Fair Housing

She/her

Robert Galbraith rob@littlesis.org

Public Accountability Initiative/LittleSis

He/him

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Maggie Corser (CPD), Robert Galbraith (LittleSis), and Natalia Renta (CPD). It was edited by Jesus Gonzalez (CPD), Jose Gonzalez (NYCC), Emily Gordon (CPD), Whitney Hu (CUFFH), Michael Kink (Strong for All), Julio López Varona (CPD), and Alicé Nascimento (NYCC). Graphic and visual design by Ange Tran (AngeTran.net).

- Renae Merle, “How one hedge fund made $2 billion from Argentina’s economic collapse,” Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Steven L. Schwarcz, “A Model-law Approach to Restructuring Unsustainable Sovereign Debt,” Centre for International Governance Innovation, Policy Brief No. 64 — August 2015, Updated October 2017, https://www.cigionline.org/static/documents/documents/PB%20no.64%20Updated_1.pdf, 3. ↑

- Astrid Iversen, ‘Vulture Fund Legislation’, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Wolters Kluwer, Vol. 38, Number 5 (March 2019) University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-57 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3456479, 1; Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697 No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 702-704. ↑

- Astrid Iversen, ‘Vulture Fund Legislation’, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Wolters Kluwer, Vol. 38, Number 5 (March 2019) University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-57 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3456479, 2-3. ↑

- Astrid Iversen, ‘Vulture Fund Legislation’, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Wolters Kluwer, Vol. 38, Number 5 (March 2019) University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-57 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3456479, 1; Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697 No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 702-704 ↑

- Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on; Mark Weisbrot and Luis Sandoval, “Argentina’s Economic Recovery Policy Choices and Implications,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, October 2007 https://www.issuelab.org/resources/711/711.pdf, 2; Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “How Hedge Funds Held Argentina for Ransom,” New York Times, April 1, 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/opinion/how-hedge-funds-held-argentina-for-ransom.html; “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=5b1623e8795e. ↑

- Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Peru, 12 F. Supp. 2d 328 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/12/328/2499011/ ↑

- Odette Lienau “Sovereign Debt, Private Wealth, and Market Failure,” Cornell Law Faculty Publications, (Winter 2020) https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2813&context=facpub, 327. ↑

- “Sovereign Debt Restructurings: Lessons learned from legislative steps taken by certain countries and other appropriate action to reduce the vulnerability of sovereigns to holdout creditors,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, October 26, 2016 https://www.un.org/en/ga/second/71/se2610bn.pdf, 10; Robin Wigglesworth, “Wins by hedge funds prompt debate on sovereign restructuring,” Financial Times, May 22, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/0395b9a4-c302-11e2-bbbd-00144feab7de. ↑

- D. Andrew Austin, “Puerto Rico’s Public Debts: Accumulation and Restructuring,” Congressional Research Service, May 18, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46788.pdf, 7-8 ↑

- Ibid, 9 ↑

- Jesse Baron, “The Curious Case of Aurelius Capital v. Puerto Rico,” New York Times, November 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/26/magazine/aurelius-capital-v-puerto-rico.html; D. Andrew Austin, “Puerto Rico’s Public Debts: Accumulation and Restructuring,” Congressional Research Service, May 18, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46788.pdf, 10. ↑

- Kate Aronoff, “Vulture Funds Stand To Make Millions In Wake Of Hurricane Maria,” The Intercept, September 28, 2018, https://theintercept.com/2018/09/28/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-recovery-funds/. ↑

- Astrid Iversen, ‘Vulture Fund Legislation’, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Wolters Kluwer, Vol. 38, Number 5 (March 2019) University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-57 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3456479, 1-2. ↑

- Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697 No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 715. ↑

- Astrid Iversen, ‘Vulture Fund Legislation’, Banking & Financial Services Policy Report, Wolters Kluwer, Vol. 38, Number 5 (March 2019) University of Oslo Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-57 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3456479, 2-3. ↑

- Daniel J. Brutti, “Sovereign Debt Crises and Vulture Hedge Funds: Issues and Policy Solutions,” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 61, Issue 5 (May 29, 2020) https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3888&context=bclr, 1831-1832. ↑

- Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Peru, 12 F. Supp. 2d 328 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/12/328/2499011/. ↑

- Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on; Stephen Kim Park, and Tim R Samples, “Towards Sovereign Equity,” Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance, Vol. 21, No 2 (2016). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2630772, 251, 253-254. ↑

- “Ad Hoc Group of Ecuador Bondholders announces support for the restructuring terms in the Republic of Ecuador’s Consent Solicitation and Invitation to Exchange relating to its outstanding sovereign bonds,” PR Newswire, July 20, 2020 https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ad-hoc-group-of-ecuador-bondholders-announces-support-for-the-restructuring-terms-in-the-republic-of-ecuadors-consent-solicitation-and-invitation-to-exchange-relating-to-its-outstanding-sovereign-bonds-301096043.html. ↑

- Tom Arnold, Karin Strohecker, “UPDATE 1-Ecuador bondholders make counter offer in $17.4 bln debt revamp,” Reuters, July 13, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/ecuador-debtrenegotiation/update-1-ecuador-bondholders-make-counter-offer-in-17-4-bln-debt-revamp-idUKL5N2EK5M5?edition-redirect=uk. ↑

- “The Republic of Ecuador Responds to Legal Action Filed by Contrarian Capital Management and GMO,” PR Newswire, July 30, 2020, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-republic-of-ecuador-responds-to-legal-action-filed-by-contrarian-capital-management-and-gmo-301102747.html. ↑

- D. Andrew Austin, “Puerto Rico’s Public Debts: Accumulation and Restructuring,” Congressional Research Service, May 18, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R46788.pdf, 9. ↑

- “Hedgepapers No. 17 – Hedge Fund Vultures In Puerto Rico,” Hedge Clippers, July 10, 2015, https://hedgeclippers.org/hedgepapers-no-17-hedge-fund-billionaires-in-puerto-rico/. ↑

- Daniel J. Brutti, “Sovereign Debt Crises and Vulture Hedge Funds: Issues and Policy Solutions,” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 61, Issue 5 (May 29, 2020) https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3888&context=bclr, 1837; Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697, No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 725-726. ↑

- “Vulture Funds in the Sovereign Debt Context,” African Development Bank Group, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/african-legal-support-facility/vulture-funds-in-the-sovereign-debt-context. ↑

- Julian Schumacher, Christoph Trebesch, and Henrik Enderlein, “Sovereign Defaults in Court,” (March 7, 2018, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189997, 12, 15. ↑

- Jeremy Bulow, Carmen Reinhart, Kenneth Rogoff, And Christoph Trebesch, “The Debt Pandemic,” Finance & Development (Fall 2020), published by International Monetary, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/09/debt-pandemic-reinhart-rogoff-bulow-trebesch.htm; “Understanding Vulture Funds,” Jubilee USA Network, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.jubileeusa.org/understanding_vulture_funds. ↑

- Julian Schumacher, Christoph Trebesch, and Henrik Enderlein, “Sovereign Defaults in Court,” (March 7, 2018, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189997, 13, 15. ↑

- Ibid, 2, 12. ↑

- “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=5b1623e8795e; Melissa Yeager, “Influence Abroad: American vulture funds feed on Argentina’s debt crisis,” Sunlight Foundation, May 2, 2016, https://sunlightfoundation.com/2016/05/02/influence-abroad-american-vulture-funds-feed-on-argentinas-debt-crisis/#head6. ↑

- Saskia Sassen, “A Short History of Vultures,” Foreign Policy, August 3, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/08/03/a-short-history-of-vultures/. ↑

- Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016,https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on; Melissa Yeager, “Influence Abroad: American vulture funds feed on Argentina’s debt crisis,” Sunlight Foundation, May 2, 2016, https://sunlightfoundation.com/2016/05/02/influence-abroad-american-vulture-funds-feed-on-argentinas-debt-crisis/#head6. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor. ↑

- Jonathan Blitzer, “Argentina’s Unending Debt,” New Yorker, April 24, 2014, https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/argentinas-unending-debt. ↑

- Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “How Hedge Funds Held Argentina for Ransom,” New York Times, April 1, 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/01/opinion/how-hedge-funds-held-argentina-for-ransom.html; Daniel Fisher, “Paul Singer Wins Long Battle With Argentina; Have Emerging Market Bonds Hit Bottom?,” Forbes, February 29, 2016https://www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2016/02/29/paul-singer-wins-long-battle-with-argentina-have-emerging-market-bonds-hit-bottom/?sh=181143051b8e. ↑

- Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Peru, 12 F. Supp. 2d 328 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/12/328/2499011/. ↑

- Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Creating a Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring that Works,” May 2016, appearing in the book: Too Little, Too Late (pp.3-32); Elliott Assocs. v. Republic of Peru, 194 F.3d 363 (2d Cir. 1998), https://casetext.com/case/elliott-associates-lp-v-banco-de-la-nacion. https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/Ch.1%20-%20Guzman-Stiglitz%20UPDATED.pdf, 12-13. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor; Michelle Celarier, “When Hedge Funds Hide,” Institutional Investor, Apr. 18, 2018, https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b17tt5rp63wvgp/when-hedge-funds-hide; Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Creating a Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring that Works,” May 2016, appearing in the book: Too Little, Too Late (pp.3-32) https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/Ch.1%20-%20Guzman-Stiglitz%20UPDATED.pdf, 13. ↑

- “The Republic of Ecuador Responds to Legal Action Filed by Contrarian Capital Management and GMO,” PR Newswire, July 30, 2020, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-republic-of-ecuador-responds-to-legal-action-filed-by-contrarian-capital-management-and-gmo-301102747.html. ↑

- Katia Porzecanski and Nathan Gill, “GMO Settles With Ecuador Over Bonds That Defaulted in 2009,” Bloomberg, April 1, 2015, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-01/gmo-settles-with-ecuador-over-bonds-defaulted-on-six-years-ago. ↑

- Odette Lienau “Sovereign Debt, Private Wealth, and Market Failure,” Cornell Law Faculty Publications, (Winter 2020) https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2813&context=facpub, 327. ↑

- Ibid, 335. ↑

- United Nations, “Report of the independent expert on the effects of foreign debt and other related international financial obligations of States on the full enjoyment of all human rights, particularlyeconomic, social and cultural rights,“ April 29, 2010, https://www.undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/A/HRC/14/21, 8. ↑

- “Democratic Republic of the Congo, Conflict in the Kivus,” International Committee of the Red Cross, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://casebook.icrc.org/case-study/democratic-republic-congo-conflict-kivus. ↑

- Jesse Baron, “The Curious Case of Aurelius Capital v. Puerto Rico,” New York Times, November 26, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/26/magazine/aurelius-capital-v-puerto-rico.html. ↑

- Daniel J. Brutti, “Sovereign Debt Crises and Vulture Hedge Funds: Issues and Policy Solutions,” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 61, Issue 5 (May 29, 2020) https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3888&context=bclr 1833; Natalia Renta, Maggie Corser, and Saqib Bhatti “PROMESA Has Failed: How a Colonial Board is Enriching Wall Street and Hurting Puerto Ricans,” Center for Popular Democracy and Action Center on Race and the Economy, September 2021, https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/%5BENGLISH%5D%20PROMESA%20Has%20Failed%20Report%20CPD%20ACRE%209-14-2021%20FINAL.pdf, 33-43. ↑

- Natalia Renta, Maggie Corser, and Saqib Bhatti “PROMESA Has Failed: How a Colonial Board is Enriching Wall Street and Hurting Puerto Ricans,” Center for Popular Democracy and Action Center on Race and the Economy, September 2021, https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/%5BENGLISH%5D%20PROMESA%20Has%20Failed%20Report%20CPD%20ACRE%209-14-2021%20FINAL.pdf 38. ↑

- Julian Schumacher, Christoph Trebesch, and Henrik Enderlein, “Sovereign Defaults in Court,” (March 7, 2018, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189997, 13, 15. ↑

- “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=5b1623e8795e. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor; Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on. ↑

- Daniel J. Brutti, “Sovereign Debt Crises and Vulture Hedge Funds: Issues and Policy Solutions,” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 61, Issue 5 (May 29, 2020) https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3888&context=bclr, 1819-1820; citing the original: Agustino Fontevecchia, The Real Story of How a Hedge Fund Detained a Vessel in Ghana andEven Went for Argentina’s Air Force One, FORBES (Oct. 5, 2012), https://www.forbes.com/sites/afontevecchia/2012/10/05/the-real-story-behind-the-argentine-vessel-in-ghana-and-how-hedge-funds-tried-to-seize-the-presidential-plane/?sh=53b5d17625aa; Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,” Washington Post, March 29, 2016,https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on. ↑

- Jonathan Blitzer, “Argentina’s Unending Debt,” New Yorker, April 24, 2014, https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/argentinas-unending-debt; Daniel Fisher, “Paul Singer Wins Long Battle With Argentina; Have Emerging Market Bonds Hit Bottom?,” Forbes, February 29, 2016https://www.forbes.com/sites/danielfisher/2016/02/29/paul-singer-wins-long-battle-with-argentina-have-emerging-market-bonds-hit-bottom/?sh=181143051b8e. ↑

- “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=5b1623e8795e; Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor. ↑

- “About Board of Trustees,” Manhattan Institute website, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/board-of-trustees; Abby Scher, “The Attack on Unions Right-Wing Politics and Democratic Possibilities,” Political Research Associates, August 1, 2011, https://politicalresearch.org/2011/08/01/the-attack-on-unionsright-wing-politics-and-democratic-possibilities; “Manhattan Institute for Policy Research,” SourceWatch, last updated April 21, 2019,https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Manhattan_Institute_for_Policy_Research; Kert Davies, “Who is Paying For Heartland Institute Climate Denial-Palooza?” Climate Investigations Center, March 24, 2017https://climateinvestigations.org/who-is-paying-for-heartland-institute-climate-denial-palooza/; “The Manhattan Institute for Policy Research: Koch Industries Climate Denial Front Group,” Greenpeace, Accessed November 15, 2021,https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/ending-the-climate-crisis/climate-deniers/front-groups/the-manhattan-institute-for-policy-research/ “Mitt Romney’s hedge fund kingmaker,” Fortune, March 26, 2012, https://fortune.com/2012/03/26/mitt-romneys-hedge-fund-kingmaker/. ↑

- Owen Davis, “Paul Singer’s Reputation Destroyed By Admission That He Played Keys In An All-White Reggae Band,” Dealbreaker, June 7, 2017 https://dealbreaker.com/2017/06/paul-singers-reputation-destroyed-by-admission-that-he-played-keys-in-an-all-white-reggae-band. ↑

- Tim Dickinson, “Right-Wing Billionaires Behind Mitt Romney,” Rolling Stone, May 24, 2012 https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/right-wing-billionaires-behind-mitt-romney-190504/. ↑

- “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=6add3bdc795e. ↑

- An act to amend the banking law, in relation to restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt, S. 6627, 2021-2022 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S6627↑

- Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697 No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 725-726. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Sarah Babb and Alexander Kentikelenis, “International Financial Institutions as Agents of Neoliberalism,” in The SAGE Handbook of Neoliberalism, edited by D. Cahill, M Cooper, M. Konings, and D Primrose, http://www.kentikelenis.net/uploads/3/1/8/9/31894609/babbkentikelenis2018-international_financial_institutions_as_agents_of_neoliberalism.pdf, 1. ↑

- Julian Schumacher, Christoph Trebesch, and Henrik Enderlein, “Sovereign Defaults in Court,” (March 7, 2018, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189997, 3. ↑

- Ross P. Buckley, “The Facilitation of the Brady Plan: Emerging Markets Debt Trading From 1989 to 1993,” Fordham International Law Journal Vol. 21, Issue 5, Article 6, (1997), https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1581&context=ilj, 1803. ↑

- Gideon Long, “Ecuador basks in glow of debt-restructuring success,” Financial Times, September 6, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/1dd975c9-e3a1-4fcc-b049-f29dbd59f6fa. ↑

- Kristalina Georgieva, “IMF Executive Board Approves 27-month US$6.5 billion Extended Fund Facility for Ecuador,” September 30, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/10/01/pr20302-ecuador-imf-executive-board-approves-27-month-extended-fund-facility. ↑

- Wilma Salgado, “Ecuador: Society’s Reaction to IMF Austerity Package,” NACLA, October 14, 2019 https://nacla.org/news/2019/10/14/ecuador-societys-reaction-imf-austerity-package-indigenous. ↑

- “Ecuador to halve fiscal deficit in 2022, president says,” Reuters, September 2, 2021 https://www.reuters.com/article/ecuador-economy/ecuador-to-halve-fiscal-deficit-in-2022-president-says-idUSL1N2Q41NO. ↑

- Michael L. Smith, “Peru Sets Austerity Measures,” Washington Post, August 10, 1990, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/08/10/peru-sets-austerity-measures/98eec033-b406-4a3b-a0b9-b7496cfbdd9a/. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor. ↑

- Natalia Renta, Maggie Corser, and Saqib Bhatti “PROMESA Has Failed: How a Colonial Board is Enriching Wall Street and Hurting Puerto Ricans,” Center for Popular Democracy and Action Center on Race and the Economy, September 2021, https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/%5BENGLISH%5D%20PROMESA%20Has%20Failed%20Report%20CPD%20ACRE%209-14-2021%20FINAL.pdf, 27. ↑

- Ibid, 27-30. ↑

- Sergio M. Marxuach, “COFINA and the “Good Enough” Restructuring Doctrine,” Center for a New Economy, February 12, 2019, https://grupocne.org/2019/02/12/cofina-and-the-good-enough-restructuring-doctrine/. ↑

- Lucas Wozny, “National Anti-Vulture Funds Legislation: Belgium’s Turn,” Columbia Business Law Review (2017), Vol. 697 No. 2 https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/CBLR/article/view/1722/743, 728; https://www.right-docs.org/doc/a-hrc-res-27-30/. ↑

- “Vulture Funds in the Sovereign Debt Context,” African Development Bank Group, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/african-legal-support-facility/vulture-funds-in-the-sovereign-debt-context; Laura Alfaro, Noel Maure, Faisal Ahmed, “Gunboats and Vultures: Market Reaction to the “Enforcement” of Sovereign Debt,” Gunboats and Vultures, December 2007 Working paper, https://www.crei.cat/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Maurer.pdf, 19, 21-22; Julian Schumacher, Christoph Trebesch, and Henrik Enderlein, “Sovereign Defaults in Court,” (March 7, 2018, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2189997, 6-7. ↑

- “Vulture Funds in the Sovereign Debt Context,” African Development Bank Group, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/african-legal-support-facility/vulture-funds-in-the-sovereign-debt-context. ↑

- “#261 Paul Singer,” Forbes, Accessed November 15, 2021 https://www.forbes.com/profile/paul-singer/?sh=5b1623e8795e; Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” New Yorker, August 20, 2018,https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor. ↑

- Renae Merle, “How One Hedge Fund Made $2 Billion from Argentina’s Economic Collapse,”Washington Post, March 29, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2016/03/29/how-one-hedge-fund-made-2-billion-from-argentinas-economic-collapse/?noredirect=on. ↑

- Daniel J. Brutti, “Sovereign Debt Crises and Vulture Hedge Funds: Issues and Policy Solutions,” Boston College Law Review, Vol. 61, Issue 5 (May 29, 2020) https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3888&context=bclr, 1820; Luca Di Fabio, Economic Development in Argentina and Its Effect on Poverty, BORGEN PROJECT (May 17, 2018), https://borgenproject.org/economic-development-in-argentina-and-its-effect-on-poverty/. ↑

- Jonathan Kent, “Dart: billionaire’s business drives Cayman’s development boom,” The Royal Gazette, February 14, 2020, https://www.royalgazette.com/other/business/article/20200214/dart-billionaires-business-drives-caymans-development-boom/. ↑

- “Sovereign Debt Restructurings: Lessons learned from legislative steps taken by certain countries and other appropriate action to reduce the vulnerability of sovereigns to holdout creditors,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, October 26, 2016 https://www.un.org/en/ga/second/71/se2610bn.pdf, 10. ↑

- Abner Dennis and Kevin Connor, “The COFINA Agreement, Part 1: The First 40 Year Plan,” Little Sis, November 19, 2018, https://news.littlesis.org/2018/11/19/the-cofina-agreement-part-1-the-first-40-years/. ↑

- Robin Wigglesworth, “Wins by hedge funds prompt debate on sovereign restructuring,” Financial Times, May 22, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/0395b9a4-c302-11e2-bbbd-00144feab7de. ↑

- “Sovereign Debt Restructurings: Lessons learned from legislative steps taken by certain countries and other appropriate action to reduce the vulnerability of sovereigns to holdout creditors,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, October 26, 2016 https://www.un.org/en/ga/second/71/se2610bn.pdf, 10, 14.Jonathan Kent, “Dart: billionaire’s business drives Cayman’s development boom,” The Royal Gazette, February 14, 2020, https://www.royalgazette.com/other/business/article/20200214/dart-billionaires-business-drives-caymans-development-boom/. ↑

- Jonathan Kent, “Dart: billionaire’s business drives Cayman’s development boom,” The Royal Gazette, February 14, 2020, https://www.royalgazette.com/other/business/article/20200214/dart-billionaires-business-drives-caymans-development-boom/. ↑

- Katy Lederer, “Why Is a Secretive Billionaire Buying Up the Cayman Islands?,” New York Times, October 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/business/kenneth-dart-cayman-islands.html. ↑

- Mike Vogel, “His Cup Runneth Over,” Florida Trend, September 1, 2000, https://www.floridatrend.com/article/13112/his-cup-runneth-over; Katy Lederer, “Why Is a Secretive Billionaire Buying Up the Cayman Islands?,” New York Times, October 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/business/kenneth-dart-cayman-islands.html. ↑

- Robin Wigglesworth, “Wins by hedge funds prompt debate on sovereign restructuring,” Financial Times, May 22, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/0395b9a4-c302-11e2-bbbd-00144feab7de;Jonathan Kent, “Dart: billionaire’s business drives Cayman’s development boom,” The Royal Gazette, February 14, 2020, https://www.royalgazette.com/other/business/article/20200214/dart-billionaires-business-drives-caymans-development-boom/. ↑

- “# 467 Kenneth Dart,” Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/billionaires/profiles/kenneth-b-dart/. ↑

- Steven L. Schwarcz, “A Model-law Approach to Restructuring Unsustainable Sovereign Debt,” Centre for International Governance Innovation, Policy Brief No. 64 — August 2015, Updated October 2017, https://www.cigionline.org/static/documents/documents/PB%20no.64%20Updated_1.pdf, 3. ↑

- For an articulation of this framework, see Steven L. Schwarcz, “A Model-law Approach to Restructuring Unsustainable Sovereign Debt,” Centre for International Governance Innovation, Policy Brief No. 64 — August 2015, Updated October 2017: https://www.cigionline.org/static/documents/documents/PB%20no.64%20Updated_1.pdf, and Steven L. Schwarcz, “Sovereign Debt Restructuring: A Model-Law Approach,” Journal of Globalization and Development, February 4, 2016: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6185&context=faculty_scholarship. ↑

- An act to amend the banking law, in relation to restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt, S. 6627, 2021-2022 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S6627 ↑

- An act to amend the banking law, in relation to restructuring unsustainable sovereign and subnational debt, A. 7562, 2021-2022 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/a7562 ↑

- New York Judiciary Law § 489, https://codes.findlaw.com/ny/judiciary-law/jud-sect-489.html; Elliott Associates, LP v. Republic of Peru, 12 F. Supp. 2d 328 (S.D.N.Y. 1998) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/12/328/2499011/. ↑

- Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Creating a Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring that Works,” May 2016, appearing in the book: Too Little, Too Late, https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/Ch.1%20-%20Guzman-Stiglitz%20UPDATED.pdf, 12-13. ↑

- Ibid, 13. ↑

- Sheelah Kolhatkar, “Paul Singer, Doomsday Investor,” The New Yorker, Aug. 27, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/08/27/paul-singer-doomsday-investor; Michelle Celarier, “When Hedge Funds Hide,” Institutional Investor, Apr. 18, 2018, https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b17tt5rp63wvgp/when-hedge-funds-hide; ; Martin Guzman and Joseph E. Stiglitz, “Creating a Framework for Sovereign Debt Restructuring that Works,” May 2016, appearing in the book: Too Little, Too Late https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/jstiglitz/sites/jstiglitz/files/Ch.1%20-%20Guzman-Stiglitz%20UPDATED.pdf, 13. ↑

- Elvis Picardo, “Two and Twenty,” Investopedia, Updated March 3, 2021, Accessed November 15, 2021, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/two_and_twenty.asp. ↑

- An act to amend the tax law, in relation to investment management services to a partnership or other entity, S. 999, 2020-2021 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S999; An act to amend the tax law, in relation to investment management services to a partnership or other entity, A. 2195, 2020-2021 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/A2195. ↑

- An act to amend the tax law, in relation to extending the top state income tax rate, S. 2522, 2020-2021 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s2522; An act to amend the tax law, in relation to extending the top state income tax rate, A. 3352, 2020-2021 Legislative Session (2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/a3352. ↑

- Alexander Gladstone, “New York Lawmakers Float Crackdown on Hedge Funds’ Sovereign-Debt Tactics,” The Wall Street Journal, February 8, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-york-lawmakers-float-crackdown-on-hedge-funds-sovereign-debt-tactics-11612780201. ↑