Introduction

Over the last several decades, U.S. public pension funds have undergone a dramatic shift in investment strategy, with traditional stocks and bonds increasingly displaced by “alternative” investments, mainly hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled “real assets.”[1] The typical public pension fund now has nearly a quarter of its portfolio invested in alternatives[2]—structured as private, co-mingled funds that are generally less regulated,[3] more opaque, [4] volatile and, most significantly, charge much higher fees to investors.[5]

Hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real asset managers typically use the “2 and 20” fee model, charging pension funds an annual management fee equal to 2 percent of assets under management, regardless of performance, as well as a performance fee (also called carried interest) based on the profit from the investment, sometimes after a hurdle rate or high water mark[6] has been met. The performance fee usually hovers around 20 percent of annual profits.

Although some pension funds have negotiated slightly lower rates in recent years, alternatives fees remain exceedingly high, and this all but guarantees the investment manager receives fee income far exceeding that of public investments. Moreover, alternative investment managers generally do not disclose the entirety of fees charged to the investor,[7] leaving pension fund participants and taxpayers in the dark about the portion of teachers’ and public workers’ deferred wages that ends up in the pockets of investment managers.

The New York Times recently described the excessive alternative investment fee structure as “Heads We Win, Tails You Lose,” reporting that when investment managers incur significant losses, the manager “can capture 100 percent of the gross return, or investors can lose money even as fund managers line their pockets.”[8] This may explain why the most recent Forbes billionaire’s list included at least 50 U.S.-based alternative asset managers,[9] and why the top 25 hedge fund managers earned more in 2015 than all of the kindergarten teachers in the U.S. combined.[10] Alternative asset managers, enriched through the extraction of fees from public employee retirement savings, in our opinion have become the robber barons of the 21st century.

While high fees prove very beneficial to the asset managers who collect them, the impact of “2 and 20” on pension funds can be dire. Every dollar paid in fees to alternative asset managers represents a dollar that does not stay in the pension fund, earning returns and compounding year after year. For pension funds investing in fund of funds—i.e., funds that invest in other funds, thus charging the investor an additional layer of fees—the fee burden is even more pronounced.

Meanwhile, U.S. public pension funds face significant funding shortfalls, with the total unfunded liability of state and local pension plans now standing at $1 trillion.[11] States like Illinois, which in 2016 had the worst-funded pension funds in the country,[12] Pennsylvania and Michigan are now experiencing pension funding crises, with teachers, public employees, public schools and taxpayers being called upon to make up the difference.

Although some critics of public pension funds place the blame for these shortfalls on public employees and pension funds themselves, our research demonstrates that excessive fees paid to alternative investment managers are a significant contributor to funding shortfalls.

Investors paying extremely high fees on alternative investments are the status quo, but there is strong evidence to suggest these fees are unjustified; for example, a 2014 study of state pension funds concluded that pension funds that paid the highest fees as a percent of assets recorded worse investment returns, on average, compared with those paying the lowest fees.[13] Alternative fee arrangements also produce a disproportionate sharing of risk, in that downside risk exposure falls exclusively on the investor, who pays fees regardless of how well the investment performs. Yet many in the alternative investment industry insist that fees are proprietary and must remain secret,[14] while alternative asset managers amass huge fortunes based largely on the fee income they collect from investors.

Given these realities, this report proposes that public pension funds, policy makers and taxpayers can and should challenge the status quo when it comes to fees, and quantifies the positive impact that this can have on pension funding status. Specifically, this report examines the alternatives fees paid by public pension funds over the last five fiscal years, and asks: How much would these pension funds have saved if alternative fees were cut in half, and how would this impact future funding levels over the next three decades?

To answer these questions, we analyzed a set of 12 public pension funds. Together, these funds have a total of $787 billion in assets under management (AUM). Because reported fee data are often unreliable[15] and complete fee information is unknown even to the pension fund,[16]we estimated fees paid on alternative investments—i.e., hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled real assets—over the last five fiscal years, using a 1.8 and 18 model to account for the fact that some pension funds have already begun negotiating a lower rate than 2 and 20. We then proposed a hypothetical fee model of 0.9 and 9 percent, which we believe to be a more appropriate fee structure for public pension funds to pay for alternative investments, and assumed for the sake of argument a sustainable assumed rate of return of 7 percent, to estimate total savings for the pension funds in our sample.

Key Findings: “0.9 and 9” Saves the Average Pension Fund in Our Study $1.8 Billion over Five Years

Our proposed hypothetical, in which pension funds pay approximately half in fees than they currently do, demonstrates that excessive fees paid to alternative asset managers by pension funds represent a very significant cost to every pension fund in our study. Our analysis suggests that halving fees on hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets investments would have produced significant benefits for every pension fund in our study. Specifically, we found that:

- Cutting fees to hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets managers by half would have saved the 12 pension funds in our study $3.8 billion per year in alternatives fees, for a total of $19 billion over the last five fiscal years.

- The average pension fund in our study would have saved an estimated $317 million per year by cutting alternatives fees in half, or $1.6 billion over the last five fiscal years.

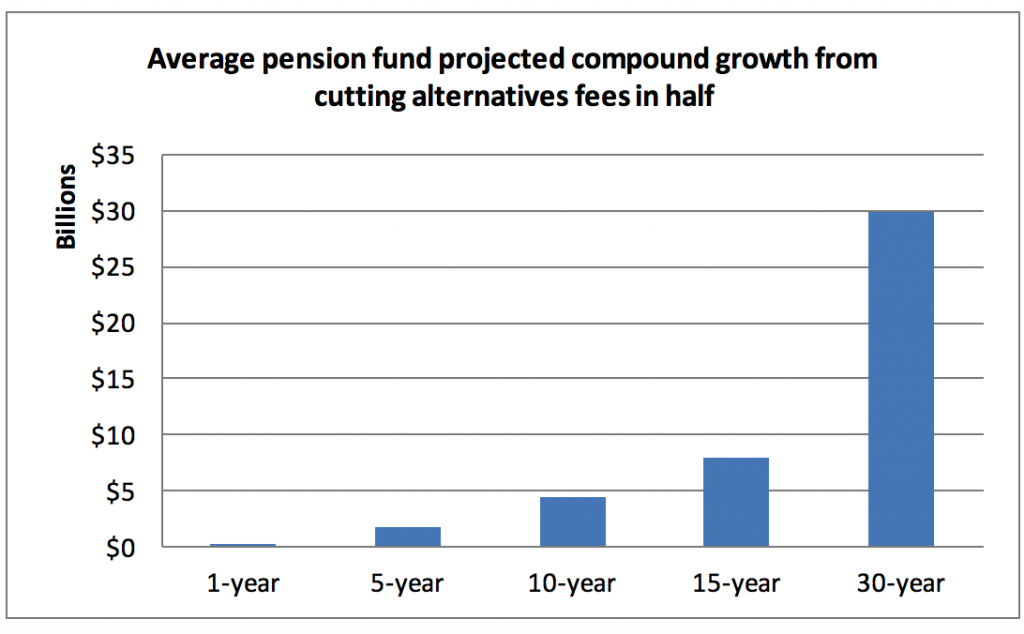

- Reducing the alternatives fee structure to 0.9 and 9 has a significant impact on the funded status of pension funds. We estimate that the average pension fund will save an additional $1.8 billion five years after adopting 0.9 and 9, $8 billion after 15 years, and $30 billion after 30 years.

Our analysis demonstrates clearly that alternative investment fees are a main contributor to the pension funding crisis. We quantify not only the hundreds of billions of dollars that public pension funds have paid in fees to alternative asset managers over the last five years, but calculate how a hypothetical, reasonable fee structure of 0.9 and 9 would contribute to improved funded status going forward. Our recommendations call on pension fund staff and trustees to take specific steps to reduce the current excessive alternative fee structure in order to reverse the transfer of wealth from middle-class workers and their retirement savings to Wall Street billionaires, including:

- Disinvestment and reallocation. Immediately begin the process of divesting from fund of funds, which represent the most costly type of alternative investment due to the additional layer of fees charged to the investor.

- Adopt policies requiring full accounting, management and disclosure of all fees by alternative investment managers, including management fees, performance fees and all other fees, to improve fee management. This fee disclosure should be provided from the inception of each alternative investment, and should be made publicly available. Pension funds should also require that all alternatives managers provide annual financial statements that include operating expenses.

- Fee limits. Adopt specific policies with respect to acceptable fee limits, with fees not to exceed 0.9 percent for management and 9 percent for performance. We encourage pension funds to consider lowering fees even further, exploring or developing alternative fee structures, along with hurdle rates and high water marks that ensure the pension fund is sufficiently compensated for the risks it takes as an investor in alternatives.

- Fee compilation. Support the development of a nonprofit organization to which pension funds can report all fees paid to investment managers and fee terms by investment manager, to promote market efficiency in the asset management industry and to correct the asymmetry of information and misaligned incentives between pension funds and alternatives managers. The nonprofit organization would make this data publicly available without naming each pension fund. Such an arrangement would essentially promote collective bargaining power for public pension funds on fees charged.

- Develop and support legislative policies that require annual public disclosure of all fees by fund and by asset manager, and that place a cap on fees paid to asset managers to ensure that taxpayers are not shouldering a disproportionate burden of the costs of fully funding retirement security for working Americans and that Wall Street pays its fair share.

The pension “crisis”: Myth vs. reality

In the majority of U.S. states, public pension funds are significantly underfunded: According to a 2016 study by George Mason University researchers, the average U.S. public pension fund is only 75 percent funded, and the total unfunded liability of state and local pension plans stands at $1 trillion.[17] The same study found that the majority of states have a pension liability ratio of 80 percent or less.[18] While funding levels of 100 percent are not necessary for the fund to be in good health, typically the threshold for pension funds to be considered adequately funded is about 80 percent.[19]

Significant pension fund shortfalls often lead to state fiscal crises, which are now unfolding in a number of states. In Illinois, home of the worst-funded state public pension fund, Gov. Bruce Rauner enacted spending cuts to address a $6 billion budget hole, and supported legislation (which was struck down in 2015 as unconstitutional) to cut public workers’ retiree benefits.[20] Michigan public employees faced a similar threat in late 2016, when the state Senate approved legislation to force new teachers into 401(k) plans instead of the defined-benefit pension fund, as a means of addressing pension shortfalls.[21]

Similarly, CalPERS and CalSTRS, the two largest public employee pension funds in the country, are increasing contribution rates to improve pension solvency.[22] Additionally, in New Jersey, Gov. Chris Christie signed a state law in 2011 reducing pension benefits and raising costs for plan participants, and then refused to make the state’s required full contribution in the years to follow. [23]

Public pension funds are not alone in facing funding challenges—multiemployer pension funds (also referred to as Taft-Hartley plans) are also experiencing significant shortfalls. The Milliman consulting firm estimates that the average funding ratio of multiemployer pension plans is 75 percent,[24] and in 2016, the Department of Labor identified 175 multiemployer plans as being in “critical” status, with 75 of the funds qualifying for “critical and declining” status.[25] Currently, the Teamsters Central States Pension Fund is predicted to run out of funds completely in just 10 years,[26] and the United Mine Workers of America fund is facing insolvency.[27]

Right-leaning legislators and think tanks typically place the blame for these pension funding struggles on the pension funds themselves and the public employees who participate in them. According to the American Enterprise Institute, “Wall Street greed isn’t to blame for the public pension crisis,” tracing responsibility instead to the “faulty assumptions” of pension fund managers and actuaries.[28] The Manhattan Institute, another conservative think tank that routinely supports efforts to dismantle defined-benefit pension plans, connects unfunded pension liabilities directly to the cost of paying pension and other benefits to retirees.[29] Additionally, the public narrative about pension reform, as evidenced by accompanying legislation aiming to cut benefits and raise participants’ costs, directs blame at the presumed excessive benefits defined-benefit plans provide to retirees.

However, in many cases these funding crises are overblown, exploited by legislators and others who would prefer to move workers’ retirement savings out of public, defined-benefit pension plans and into 401(k)-style defined-contribution schemes. Although traditional pension plans are certainly facing funding challenges, defined-benefit (DB) pension plans, a category that includes most public pensions, continue to prove less costly than defined-contribution (DC) plans such as 401(k)s. According to a 2014 study of Canadian retirement plans, DB plans can be run more efficiently that DC plans, which the study found cost 77 percent more to administer.[30] A study of U.S. retirement plans conducted the same year found that, owing to DB plans’ lower administrative costs and higher returns, a participant in a DB plan will have 25 percent more after 25 years than a participant in a DC plan.[31]

Notably, these critiques ignore one significant reason for the poor funding status of many public pension plans: the failure of the sponsor (e.g., the state or municipality) to pay the actuarial required contribution, as has occurred in places like Illinois and New Jersey. In addition to the persistent and purposeful underfunding of pension funds by elected officials, the twin economic shocks of the dot-com bubble burst in 2000 and the Great Recession of 2008-09 also created significant losses for many public pension funds; in 2008-09 alone, nearly all public pension funds experienced a drop in funded status.[32]

Clearly, there is an ongoing debate as to what factors are responsible for pension underfunding, and while we acknowledge the roles of economic downturns and inaction by plan sponsors in reducing funded status, this report contributes to the funding debate by focusing on the role of investment fees in the pension funding crisis. Our analysis suggests that a significant contributing factor to the underfunding of pensions is the excessive fees charged to pension funds by managers of alternative investments—hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled real assets.

Both on an individual fund level and in the aggregate, our research demonstrates that alternative investments, due to their high fee structures, serve to siphon money directly out of pension funds into the hands of asset managers—and if these fees were to be reduced by half, pension funds would experience significant improvements to their funding status.

Alternative investments explained

Investments that do not fall into the categories of “traditional” investments (i.e., stocks and bonds) are usually referred to as “alternative” investments. What alternative investments have in common, besides only being available to institutional investors and very high net worth individuals, is that they typically charge much higher fees than traditional investments.[33] This report focuses on the three main types of alternative investments that public pension funds are known to invest in: hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled real assets.

In general, these three investment types use a fee structure that is known as “2 and 20.” The “2” refers to the annual management fee, which is taken off the top as 2 percent of assets managed regardless of performance. The “20” refers to the performance fee (also referred to as an incentive fee, carried interest or profit-sharing) which is taken as a percentage of profit from the investment’s performance, which usually hovers around 20 percent of profits.

Some alternative investment contracts also include hurdle rates, which stipulate that asset managers can collect a performance fee only if the fund generates a certain level of return, and high water marks, which stipulate that the fund must clear a previous level of profit reached before collecting a performance fee.

Notably, some pension funds have negotiated slightly lower fee rates in recent years, and some observers have wondered if the “2 and 20” fee structure is “over.”[34] However, any downward movement in alternative fees appears to be concentrated in hedge fund investments, where the average management and performance fees stand at 1.7 percent and 19.5 percent, respectively.[35] Recent survey data suggest that the median management and performance fees charged on private equity remain close to 2 and 20,[36] and co-mingled real estate fees have been shown to surpass those of hedge funds and private equity. [37]

It’s important to note that fees charged by alternative investment managers are not limited to management and performance fees. General Partners (GPs) routinely charge a range of additional fees—to cover administrative, legal or transaction costs, for example—back to the pension fund without clearly disclosing the amount of these fees.[38] For example, a 2014 internal review by the Securities and Exchange Commission found that half of the private equity funds reviewed charged unjustified fees and expenses to investors without their knowledge,[39] with an SEC official stating, “In some instances, investors’ pockets are being picked. These investors may be sophisticated and they may be capable of protecting themselves, but much of what we’re uncovering is undetectable by even the most sophisticated investor.”[40]

Compounding fees through fund of funds

Another layer of fees that some pension funds pay on their alternative investments comes in the form of fund of funds.

Fund of funds, which are typically used by investors that are smaller or new to alternatives, are investment types run by an asset manager, who then invests the investor’s funds in other investment funds; fund of funds are distinct within the alternative investment category in that the investor does not invest with alternative managers directly. The investor thus pays fees to the fund of funds, as well as paying the already exorbitant fees of all of the underlying funds.

An analysis by former SEC lawyer Edward Siedle calculated that the exorbitant fee structure of fund of funds is so high that the fund must earn at least a 12 percent return just to provide the investor with a return equal to the risk-free rate on Treasury bonds.[41] And in “Fees Eat Diversification’s Lunch,” researchers determined that the “benefits of a fund of funds—delegation, manager diversification, due diligence, and access—may come at such a cost as to offset the benefits of the underlying funds.“[42]

Even more troubling, pension funds and other investors are often contractually prohibited from obtaining information about these “hidden fees,” with some alternative asset managers requiring pension funds to sign contracts stating that the asset managers do not have to disclose these fees, and that pension funds do not have the right to require disclosure. These elaborate mechanisms to avoid having alternative asset managers disclose the fees themselves and to prevent pension funds from disclosing them begs the question: Why so much secrecy? What are alternative asset managers hiding?

A 2016 Pensions and Investments editorial titled “Fee Secrecy Is Wrong, Period” summed up the lack of transparency with respect to alternative investments as such:

“In moving more to alternatives, public plans have taken nearly 25 percent of their investment assets off the grid, a move that can shortchange participants, the public and sometimes trustees of important information. It is a disturbing development, especially because private equity and other alternatives are the most expensive asset classes of pension funds.”[43]

Alternative investment managers justify the fees they charge investors by claiming to provide outsized returns that offset the fees. They also claim to help diversify investor portfolios because their returns are purportedly less correlated with equity markets, thus also offering downside protection to investors. In effect, alternative asset managers suggest that when these factors are considered, the higher fees pay for themselves.

Investors have largely accepted these justifications, and paying extremely high fees on alternative investments is now the status quo among public pension funds. However, as the following sections of this report demonstrate, alternative investment fees by and large cancel out any of the purported benefits of these investments, and ultimately reduce pension funding levels, which impacts public employees, retirees and taxpayers. In short, public pension funds can and should challenge the status quo when it comes to alternatives fees, to ensure that a larger portion of workers’ retirement savings stay in the pension fund and do not end up in the pockets of investment managers.

Pension funds doubling down on alternatives—but who benefits??

According to a recent survey, the average public pension fund has 24.1 percent of its portfolio invested in alternatives, defined as hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled real assets.[44] This represents a significant increase in alternatives from just a few years ago; according to a 2014 report, from 2006 to 2012, U.S. public pension funds’ allocation to alternatives more than doubled, from 11 percent to 23 percent over this six-year period.[45]

Many observers explain this rapid increase in alternative investment allocations as a response to two significant economic downturns, first the dot-com stock crash of 2000, then the Great Recession, both of which left many pension funds with significant losses—and this prompted funds to seek ways to further diversify their portfolios to protect against future losses. Thus, following these economic events, pension funds turned increasingly to alternative investments, with their promises to outperform the market and provide uncorrelated returns.

Unfortunately, alternative investments did not always perform as promised, especially after accounting for fees, as we explored in our previous report “All That Glitters Is Not Gold,” which examined the experience of a set of pension funds with hedge fund fees and returns, and found that hedge funds failed to deliver any significant benefits to any of the pension funds we reviewed. Specifically, our analysis found that the average pension fund paid 59 cents in fees to hedge fund managers for every dollar of net return to the fund.[46]

Private equity firms have generally reported more robust returns than hedge funds, but the veracity of their reported returns has been routinely called into question on a number of fronts, including the accuracy of reporting methods and the question of inflated valuations. Private equity firms usually rely on the internal rate of return (IRR) method to calculate returns, which computes returns on an annual basis, rather than on a since-inception basis. This results in these firms reporting inflated returns, often by 25 percent or more, by shortening the amount of time an investor’s money is deployed.[47] In fact, a 2007 study published in the Harvard Business Review found that IRR typically results in private equity firms reporting their returns to be twice as high as they actually are, concluding that “Overstated private equity performance may partially explain why investors continue to allocate substantial capital to this asset class.”[48]

A more recent review by the Center for Economic and Policy Research states that “private equity performance that appears acceptable when measured by a fund’s internal rate of return may actually underperform public equities,” suggesting that private equity returns may not produce high enough returns to warrant their high cost.[49]

Like private equity, co-mingled real assets also appear to produce higher returns than hedge funds in general, but the excessive fees associated with real assets investments may outweigh the benefits of these returns. In a 2016 article in Forbes, Edward Siedle identifies nine different types of fees typically charged by real assets managers beyond management and performance fees, including acquisition, financing and brokerage fees, and fund operating expenses. Siedle estimates that these fees can amount to an additional 3 percent above and beyond the typical fees reported by pension funds.[50]

Given the excessive fees charged and the questionable returns produced by alternative investments, it is reasonable to ask who benefits from placing such large portions of public pension funds into alternatives—the pension funds, or the asset managers? Research suggests that this arrangement overwhelmingly benefits the latter:

- A 2014 study of state pension funds concluded that pension funds that paid the highest fees as a percent of assets recorded worse investment returns, on average, compared with those that paid the lowest fees.[51]

- According to Simon Lack, author of The Hedge Fund Mirage, from 1998 to 2010, hedge fund managers kept a full 84 percent of returns, leaving investors with only 16 percent; when taking fund of funds into account, a full 98 percent of total returns went to the hedge fund managers, with investors seeing only 2 percent.[52]

- According to a recent report in Pensions and Investments, “Average hedge fund returns have since declined, yet fees, like an object thrown into space, have continued to levitate without gravity to pull them down. This is now changing as more investors realize the 2/20 structure doesn’t make sense at today’s return levels. … [With annual HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index returns of around 5 percent today], less than half (about 48 percent) of the returns the manager generates go to the investor under a 2/20 fee structure.”[53]

- As a Forbes analyst concludes:

“These fee arrangements are a wealth transference mechanism, systematically moving money from investors to hedge-fund managers.” [54]

Another analyst suggests that private equity management fees alone are enough to make private equity managers “very rich” if their funds grow to a sufficient size, regardless of their performance, suggesting a misalignment of interests.[55]

The cost of alternatives to pension funds

As the studies outlined above suggest, alternative investments charge extraordinarily high fees to pension funds—and these costs are not easily justified by returns. Additionally, because all of the risk lies with the investors, who pay fees even if the investment loses money, it is difficult to defend the high cost of alternative investments on the basis of diversification or downside protection. As the authors of “Fees Eat Diversification’s Lunch ” put it: “[I]nvestment management fees are a certain dead-weight loss, whereas the riskiness of the diversification benefit remains.”[56] Although the fee arrangement certainly benefits the asset manager, the benefit to pension funds—and by extension to public employees, retirees and taxpayers—is far from clear.

Despite these many reasons to question the validity of the 2-and-20 fee structure, alternative investment fees have remained exorbitantly high for nearly three decades. One factor that contributes to this is the culture among pension funds, promulgated by consultants and investment managers, that promotes acting in isolation from—and often in competition with—other pension funds on the question of fees. This, combined with the extreme lack of transparency on behalf of the alternative investment industry,[57] makes it nearly impossible for pension funds to assess their costs and negotiate better contract terms.

We believe that pension funds can in fact find common purpose in addressing fees, and can take collective action to demand an end to “2 and 20.” In fact, our analysis demonstrates that a fee structure of 0.9 and 9 would not only save the average pension fund hundreds of millions of dollars per year in fees and improve funded status, but would also reduce the transfer of wealth from working people to Wall Street’s wealthiest players.

Proponents of the status quo will argue that pension funds lowering fees on alternative investments will preclude them from access to the “best” funds that produce the highest returns. However, extreme opacity when it comes to alternative investment fees makes these claims difficult to evaluate. There is scant evidence that fees are correlated with performance–and in fact the opposite appears to be true.[58] Moreover, a few pension funds have already taken steps to reduce some alternative investment fees, with no discernable negative impacts. Thus we believe our hypothetical fee structure of 0.9 and 9 to be appropriate and reasonable.

The remainder of this report outlines our analysis of how alternative investment fees have impacted public pension funds, and how reducing fees on these investments can improve the funded status of pension funds.

Our findings

Data Sources

We analyzed a set of 12 public pension funds, with a total of approximately $787 billion in assets under management (AUM), and $135 billion in hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets AUM combined as of the most recent fiscal year reported. The pension funds included in this analysis are:

- Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island (ERSRI)

- Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Management Board (PRIM)

- Michigan State Employees’ Retirement System (MSERS)

- Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System (MPSERS)

- New Jersey Pension Fund

- New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS)

- New York State Common Retirement Fund (New York Common)

- Ohio Public Employees Retirement System (OPERS)

- Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS)

- Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System (Pennsylvania SERS)

- Teacher Retirement System of Texas (TRST)

- Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois (Illinois TRS)

We selected these funds based on a combination of size of assets under management, availability of net return data for alternative investments, and the degree to which the state where the pension fund is located is experiencing pension funding shortfalls or other budget deficits that may impact the pension fund. The average pension fund in this group had $65.6 billion in total fund AUM and $11.2 billion in alternatives AUM for the most recent fiscal year reported.

We obtained AUM and net return data for each pension fund’s hedge fund, private equity, co-mingled real assets and total fund investments from the following sources: comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) for the pension funds, investment reports, websites and/or public records requests. For each pension fund, we used fiscal year-end data reflecting the previous 12-month period.

Methodology

This report assesses the impact of alternatives fees on public pension funds in two ways. First, we estimate how much public pension funds paid in hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets fees over the five most recent fiscal years, and how much the pension funds would have saved if the fee rate were halved. Second, we use the average estimated alternatives fees paid per year by the pension funds to perform a forward-looking projection of the savings incurred by cutting fees in half, compounding annually, and how that would improve funding levels.

Hedge fund, private equity and real asset managers typically do not disclose comprehensive information related to the fees they charge pension funds (and other institutional investors). When managers do disclose these fees, the figures are often incomplete because they fail to account for all types of fees (management, performance and so-called hidden fees). Moreover, it is not uncommon for the pension funds themselves to lack access to complete fee data because alternative investment contracts sometimes preclude the pension funds from requesting this information.[59]

An additional obstacle to obtaining alternative investment fee data from pension funds is the complexity in how the fees are structured and collected. Information regarding hurdle rates, high water marks and frequency of fee collection is not publicly available, and to date no infrastructure exists to collect that data systematically. Absent transparency on costs, it is impossible to produce a precise, detailed and accurate analysis of fees paid on hedge fund, private equity and real asset investments by public pension funds, and hence impossible to truly assess whether the costs of alternatives are worth the benefits they claim to provide.

For these reasons, this analysis uses the following methodology to estimate fees:[60]

- Gross returns are calculated using the following assumptions:

- Alternative investment management fees are calculated conservatively at an annual rate of 1.8 percent of assets under management (AUM).

- Alternative investment incentive fees are calculated conservatively at 18 percent of gross return less management fees.

We estimate alternatives fees at 1.8 percent and 18 percent to reflect the fact that some pension funds pay fee structures that are slightly lower than the traditional 2 and 20 on some alternative investments. For more information on how we arrived at 1.8 and 18, see the Appendix.

- Performance fees were adjusted to $0 for fiscal years where net returns were negative.

- Performance fees were also adjusted for fiscal years where hurdle rates were not met. We assumed hurdle rates of 7 percent for all hedge fund investments, 8 percent for private equity investments and 8.7 percent for real assets, calculated using gross returns.

- For forward-looking projections, we used an assumed rate of return of 7 percent, and a redistribution of the fund’s historic allocation to alternatives in line with the fund’s existing asset allocation.

These assumptions and calculations are intended to provide an informed estimate of fees and savings resulting from a reduction in these fees. It is incumbent upon pension funds and their investment consultants to review actual contract terms that define management and incentive fees as well as hurdle rates (if any) to more precisely calculate the total fees captured by asset managers.

Key findings

Our analysis suggests that halving fees on hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets investments would have produced significant benefits for every pension fund in our study. Specifically, we found that:

- Cutting fees to hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets managers by half would have saved the 12 pension funds in our study $3.8 billion per year in alternatives fees, for a total of $19 billion over the last five fiscal years.

- The average pension fund in our study would have saved an estimated $317 million per year by cutting alternatives fees in half, or $1.6 billion over the last five fiscal years.Reducing the alternatives fee structure to 0.9 and 9 has a significant impact on the funded status of pension funds. We estimate that the average pension fund will save an additional $1.8 billion five years after adopting 0.9 and 9, $8 billion after 15 years, and $30 billion after 30 years.

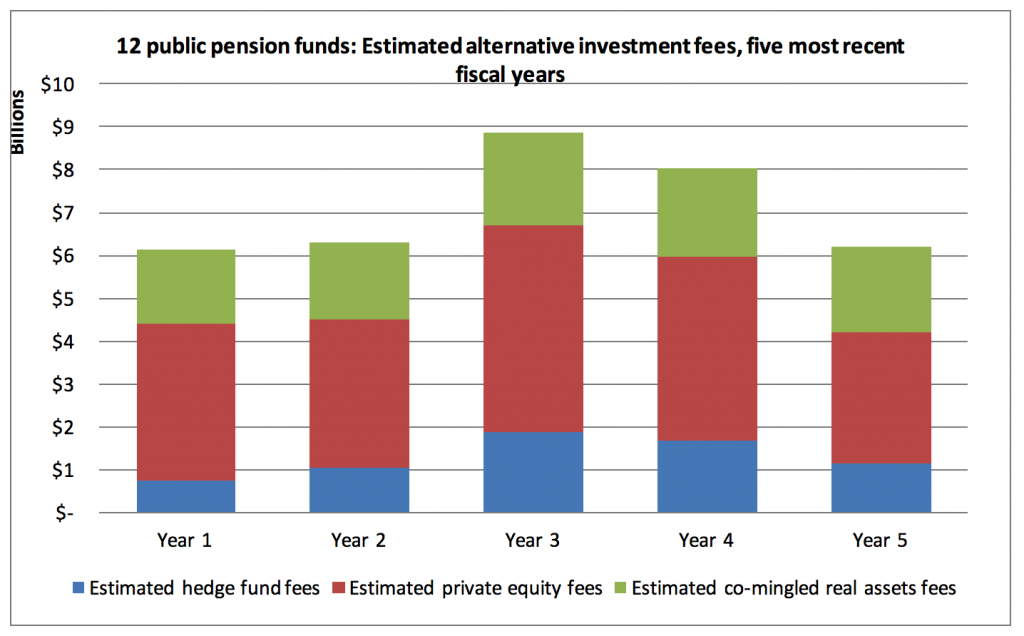

According to our estimates, alternative asset managers collected $35.5 billion in fees from the 12 pension funds in our study over the previous five years, as illustrated in this chart:

As we outlined in previous sections of this report, every dollar paid in fees to asset managers is a dollar that could be reinvested and compounded year in and year out. Therefore, if the 12 pension funds in our study had adopted a 0.9 and 9 fee structure over the last five fiscal years, essentially reducing alternatives fees by half, these funds collectively would have an additional $19 billion in funding available to pay benefits and contribute to improved funding status.

The 12 pension funds in our report represent a reliable sample of large U.S. public pension funds. With total AUM ranging from $8 billion to $179 billion, the average pension fund in our sample has $65.6 billion in AUM and $11.2billion invested in alternatives. (For more detailed data on the average and median fund in our study, see the Appendix).

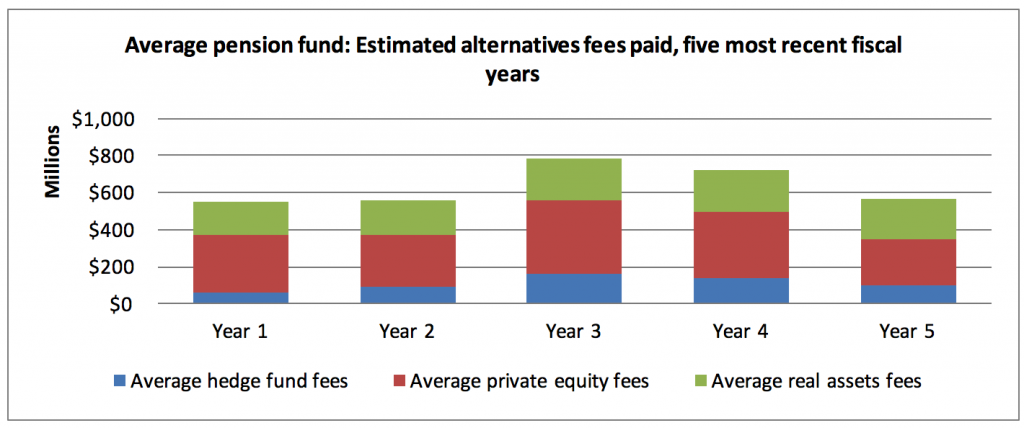

According to our estimates, the average fund in our study paid an estimated $592 million in alternatives fees per year over the last five years, as illustrated in the following chart:

In total, the average pension fund paid an estimated $3 billion in alternatives fees over the five most recent fiscal years, assuming a fee structure of 1.8 and 18. However, if the average pension fund in our study were to reduce its alternatives fee structure to 0.9 and 9, the savings would be significant. Not only would the amount paid in fees to Wall Street investment managers decrease by half, but the money saved on fees would compound, resulting in even greater growth. In fact, if the average pension fund in our study had adopted 0.9 and 9 over the last five fiscal years, we estimate that it would have an additional $1.6 billion in funding available to invest and grow.

While it is useful to estimate the amounts that pension funds paid in alternatives fees over the last five years, and how much the funds would have saved if they had negotiated lower fees, it is also useful to perform a forward-looking analysis of how assets under management (AUM) will grow in the future if they were to implement 0.9 and 9 this year. Using average alternatives fees paid over the five most recent fiscal years, and assuming a rate of return of 7 percent, we estimate compounded savings from cutting alternatives fees in half over one-, five-, 10-, 15- and 30-year periods for the average pension fund in our study, as illustrated in the following table:

Alternative investments managers claim that pension funds lowering the amount of fees they are willing to pay on hedge funds, private equity and co-mingled real assets will preclude them from accessing the best alternative asset managers, i.e., those who are able to produce returns high enough for the pension fund to meet an assumed rate of return of 7 percent. However, there is little evidence suggesting that fees are correlated to performance—and the fact that pension funds such as the New Jersey Pension Fund and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas already have taken steps to lower hedge fund fees, with no immediately discernable negative impacts, suggests that the investment managers’ claims that lower fees will lead to lower returns are largely not credible for hedge funds.

Considering that the average pension fund in our study retains $1.8 billion in the first five years alone after reducing alternatives fees to 0.9 and 9 percent—with 30-year growth reaching $30 billion—all public pension funds should assess their alternatives program and demand lower fee arrangements on hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets investments as an important strategy to improve funded status.

Case studies

Of the 12 pension funds in our sample, we selected three for individual case studies: Illinois TRS, Michigan PSERS and Pennsylvania PSERS. We chose these pension funds because they are located in states facing budget shortfalls and/or states where legislators are proposing cuts or changes to the pension funds as a way to address budget issues. These three pension funds also all have significant investments in alternatives, therefore they provide an opportunity to demonstrate how alternatives deplete pension funds, and how reducing these fees by half significantly improves funding status in the future—both near- and long-term.

Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois

Illinois is facing a budget crisis, with Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner enforcing spending cuts to address a $6 billion budget hole, and proposing significant cuts to public employees’ retirement benefits.[61] Compounding the budget issues is the fact that state lawmakers refused to make the annual required payments into the state pension fund for years, and now Illinois’ pension funds are the worst-funded in the country, with a funding ratio of only 42 percent.[62] Illinois TRS’ unfunded liability was $73.4 billion at the end of 2016.[63]

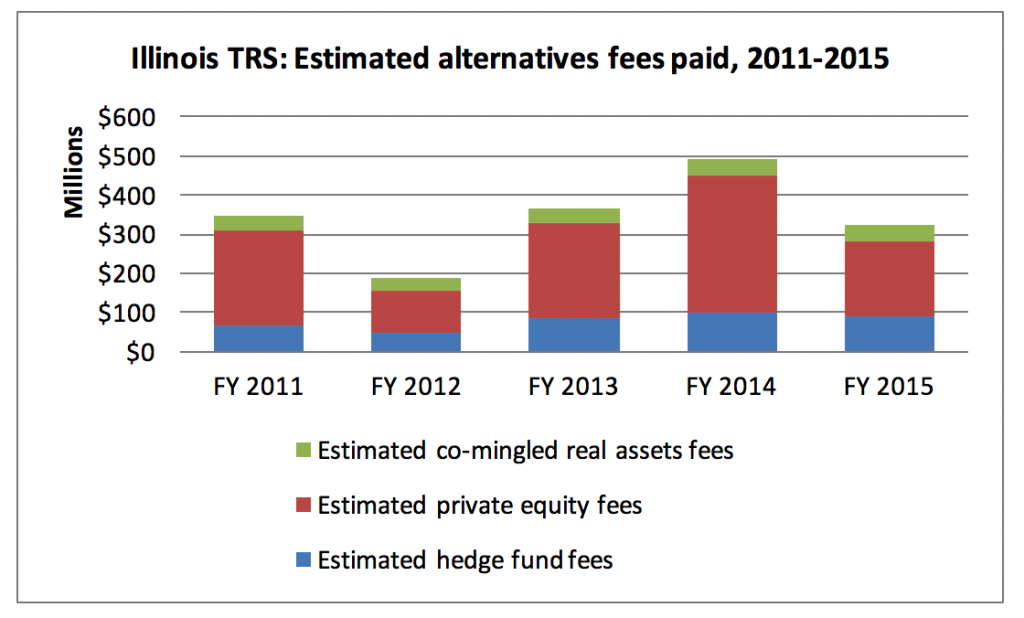

Our analysis demonstrates that a significant contributor to the pension fund’s unfunded liabilities is disproportionately high fees paid to alternative asset managers. The Illinois TRS, one of the Illinois state pension funds, has approximately $10 billion—or over one-fifth of its portfolio—invested in alternatives, according to the most recent fiscal-year data available, and we estimate that the pension fund paid on average $344 million per year in fees to hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets managers between fiscal years 2011 and 2015. If Illinois TRS had reduced its alternative fee structure to 0.9 and 9, it would have saved more than $860 million over this same period, mitigating the current funding crisis.

According to our estimates, Illinois TRS paid $1.7 billion in alternatives fees from 2011-15:

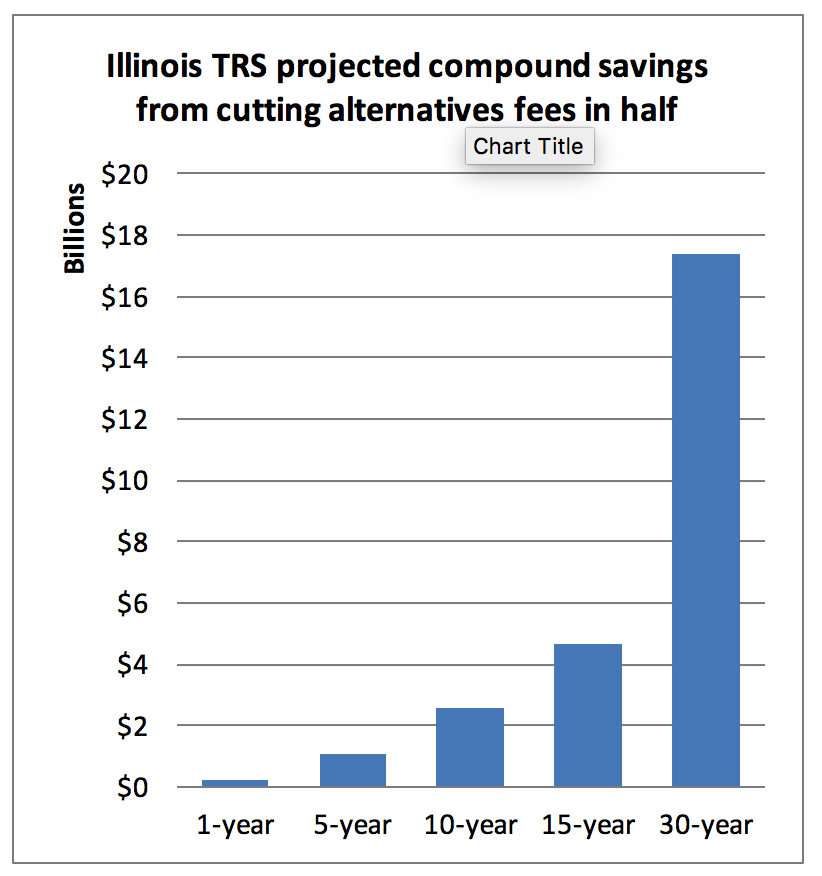

If Illinois TRS were to cut alternative fees in half—paying 0.9 and 9 instead of the estimated 1.8 and 18—the pension fund would save an estimated $184 million in the first year alone. These savings would be reinvested and compound over time, with Illinois TRS having an additional $17.4 billion in the fund after 30 years, significantly improving funded status.

Given these projections, legislators and other stakeholders aiming to address the funding issues facing pension funds in Illinois should carefully examine the exorbitant fees the pension funds paid their alternative asset managers and support efforts to reduce these fees by at least half, in order to maintain more money in the fund to pay benefits, and to stem the flow of workers’ retirement savings to Wall Street.

Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System (MPSERS)

In the 1990s, Michigan became the first state to close its public pension fund to new state workers, forcing them to enter a 401(k)-style retirement fund instead of a defined-benefit pension fund. Now, Republican lawmakers in the state are advocating that the same be required of new teachers, proposing legislation to close the teacher pension funds, MPSERS, to new members as a means of addressing the pension fund’s unfunded liability,[64] which stood at $26.7 billion in 2015.[65]

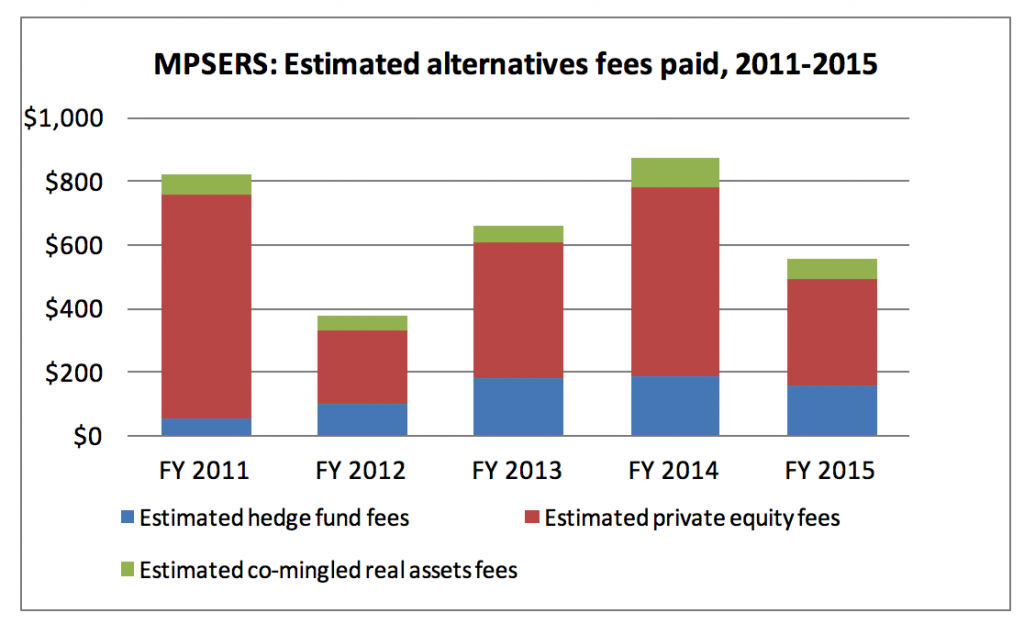

Our analysis demonstrates that a significant contributor to MPSERS’ unfunded liabilities is disproportionately high fees paid to alternative asset managers. MPSERS has approximately $16 billion—more than one-third of its portfolio–invested in alternatives, according to the most recent fiscal-year data available, and we estimate that the pension fund paid on average $658 million per year in fees to hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets managers between fiscal years 2011 and 2015. If MPSERS had reduced its alternative fee structure to 0.9 and 9, it would have saved an estimated $1.6 billion over this same period, mitigating the current funding crisis.

According to our estimates, MPSERS paid $3.3 billion in alternative investment fees over the last five years:

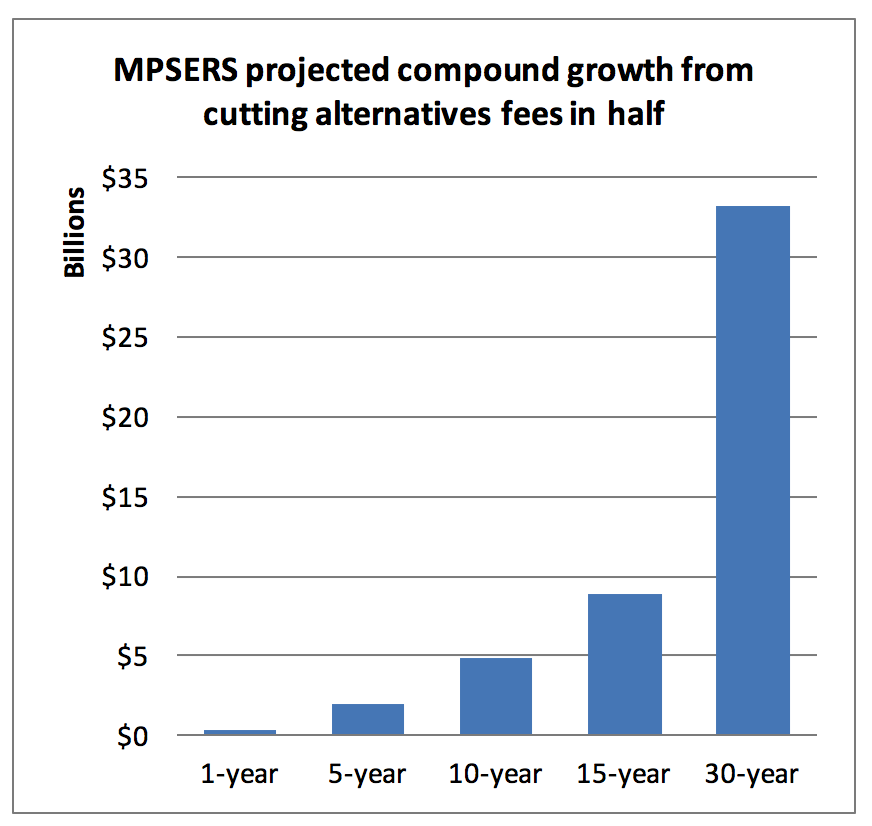

If MPSERS were to cut alternative fees in half—paying 0.9 and 9 instead of the estimated 1.8 and 18—the pension fund would save an estimated $352 million in the first year alone. These savings would be reinvested and compound over time, with MPSERS having an additional $33 billion in the fund after 30 years, significantly improving funded status.

Given these projections, legislators and other stakeholders aiming to address the funding issues facing pension funds in Michigan should carefully examine the exorbitant fees the pension funds paid to alternative asset managers, and support efforts to reduce these fees by at least half, in order to maintain more money in the fund to pay benefits, and to stem the flow of public workers’ retirement savings to Wall Street.

Pennsylvania Public School Employees Retirement System (PSERS)

Lawmakers in Pennsylvania, like those in Illinois, made contributions to the state pension funds that were significantly less than what was required actuarially to maintain a healthy pension fund for many years—and like their counterparts in Michigan, Republican lawmakers are proposing shifting public employees, including teachers, to defined contribution-style plans.[66] PSERS’ estimated unfunded liability as of 2015 was $37.3 billion.[67]

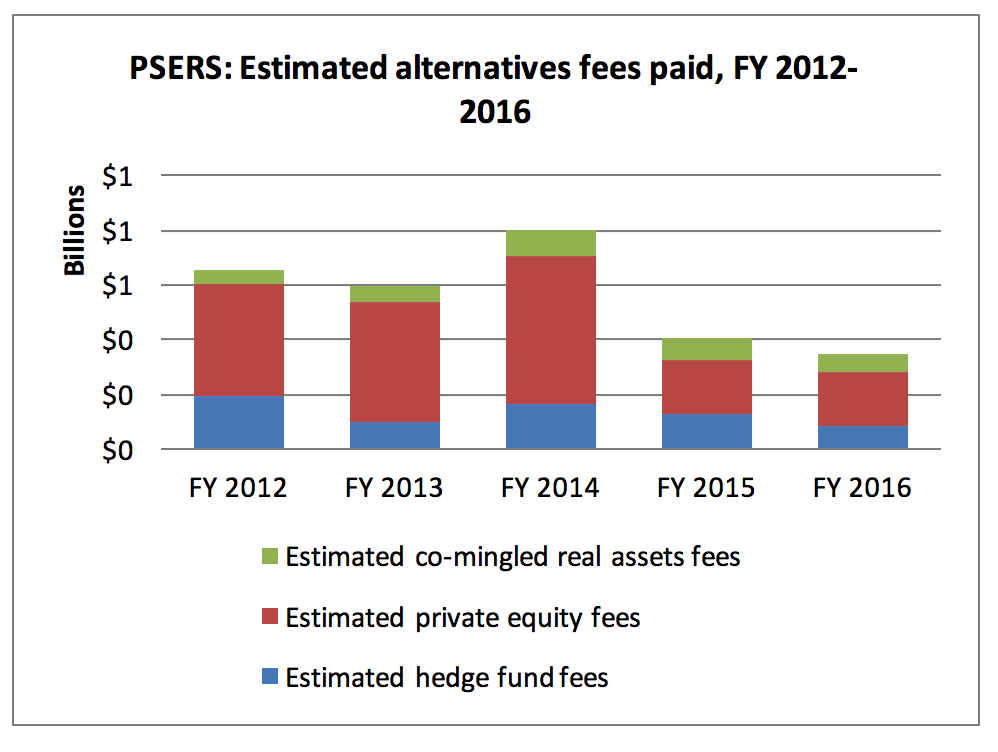

Our analysis demonstrates that a significant contributor to these unfunded liabilities is disproportionately high fees paid to alternative asset managers. PSERS, one of the two state pension funds, has approximately $14 billion invested in alternatives—nearly one-third of its portfolio—according to the most recent fiscal-year data available, and we estimate that the pension fund paid on average $560 million per year in fees to hedge fund, private equity and co-mingled real assets managers between fiscal years 2012 and 2016. If PSERS had reduced its alternative fee structure to 0.9 and 9, it would have saved more than $1.4 billion over this same period, mitigating the current funding crisis.

According to our estimates, PSERS paid $2.8 billion in alternative investment fees over the last five years:

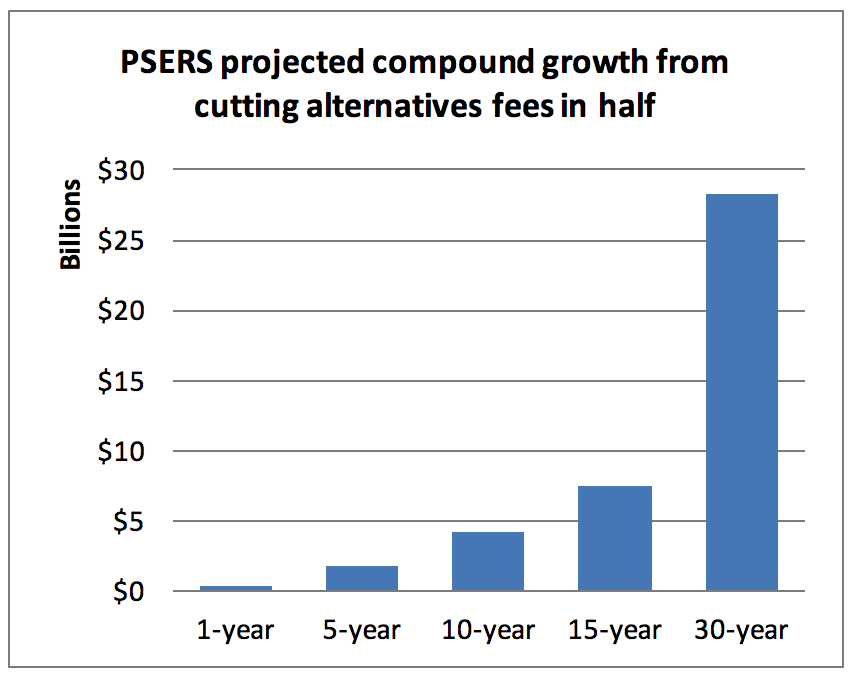

If PSERS were to cut alternative fees in half—paying 0.9 and 9 instead of the estimated 1.8 and 18—the pension fund would save an estimated $300 million in the first year alone. These savings would be reinvested and compound over time, with PSERS having an additional $28 billion in the fund after 30 years, significantly improving funded status.

Notably, PSERS has taken steps in recent years to improve transparency and to address fees. In 2015, the fund began collecting performance fee data on private equity and co-mingled real assets investments, and according to the pension fund it pays average management and performance fees of 1.38 percent 17.59 percent respectively, suggesting a slightly lower fee structure than our estimate of 1.8 and 18.

Given these projections, legislators and other stakeholders aiming to address the funding issues facing pension funds in Pennsylvania should carefully examine the exorbitant fees the pension funds paid to alternative asset managers, and support efforts to reduce these fees by at least half, in order to maintain more money in the fund to pay benefits, and to stem the flow of public workers’ retirement savings to Wall Street.

Recommendations

While the last decade saw pension funds allocating increasingly significant portions of their portfolios to alternative investments, the last couple of years have offered signs that this trend may be beginning to reverse. Last year, at a high-profile investor conference, the 2-and 20 model was in the spotlight, with Warren Buffet recommending that investors divest from all expensive asset managers, and CalSTRS CEO Chris Ailman stating that 2 and 20 is “broken” and “off the table” for large institutional investors like CalSTRS, noting that “reducing your fees is your best return on capital.”[68]

In 2016, several of the pension funds in our analysis took steps to reduce fees, including the New Jersey Pension Fund, which in August voted to cut fees on hedge fund investments to 1 and 10, and to cut its hedge fund allocation in half, divesting approximately $4.5 billion.[69] In December, the Teacher Retirement System of Texas adopted a “1 or 30” fee model for hedge fund investments, meant to ensure that the pension fund keeps at least 70 percent of gross returns generated.[70]

Although most alternative asset managers defend their fees as being completely justified, a few have admitted that “2 and 20” is not warranted. Cerberus Capital Management CEO Stephen Feinberg stated publicly in 2012 that private equity managers “make absurd amounts of money. We’re all overpaid. [Investors] asking for fee discounts are completely justified.”[71] And hedge fund manager Cliff Asness of AQR Capital Management recently concurred that “net as an industry, yes, fees are too high.”[72]

The imperial origins of “2 and 20”

The “2 and 20” fee structure was originated by what is believed to be the first hedge fund, established in 1949 by Alfred Winslow Jones. He based his fees on how ancient Phoenician merchants financed their expeditions,[73] charging a flat fee and then a percentage of any gold or other valuable resources they obtained.

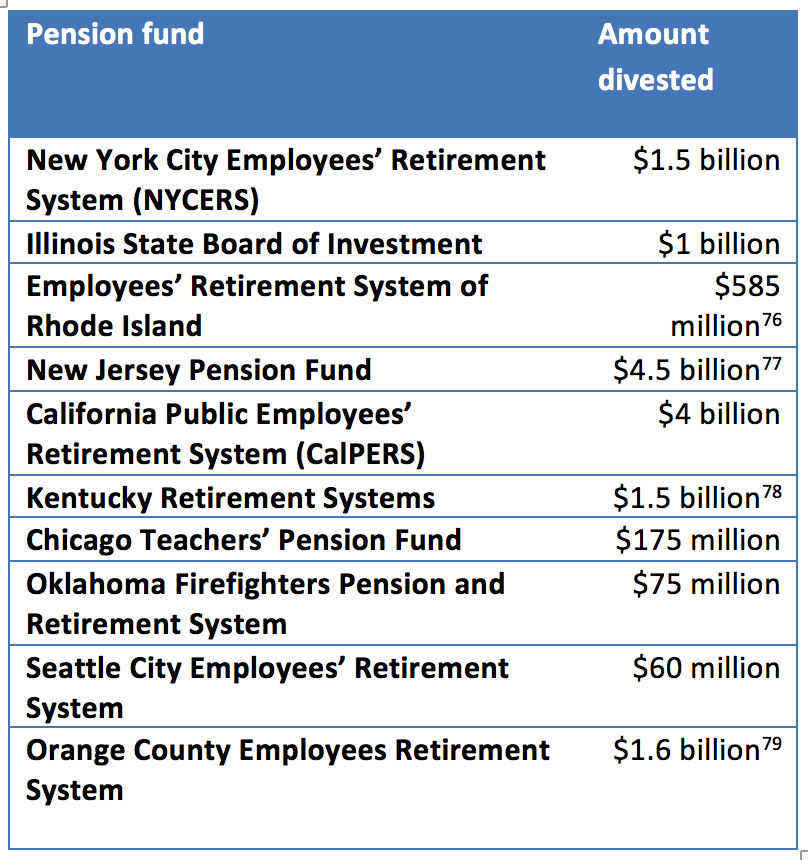

Other pension funds have acted on their concerns regarding hedge fund fees in another manner—by divesting altogether. As New York City Public Advocate Letitia James stated last April, when NYCERS voted to divest from hedge funds: “Hedges have underperformed, costing us millions. Let them sell their summer homes and jets, and return those fees to their investors.”[74] The following table shows public pension funds that are known to have significantly reduced their hedge fund investments since 2014:[75]

| Pension fund | Amount divested |

| New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS) | $1.5 billion |

| Illinois State Board of Investment | $1 billion |

| Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island | $585 million[76] |

| New Jersey Pension Fund | $4.5 billion[77] |

| California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) | $4 billion |

| Kentucky Retirement Systems | $1.5 billion[78] |

| Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund | $175 million |

| Oklahoma Firefighters Pension and Retirement System | $75 million |

| Seattle City Employees’ Retirement System | $60 million |

|

Orange County Employees Retirement System |

$1.6 billion[79]

|

In addition to divesting from hedge funds altogether or reducing fees, another way to address exorbitant alternatives fees is by reducing the number of external managers used by the pension fund—a process CalPERS began in 2015 when it announced that it was cutting its number of external managers.

In 2016, the Institutional Limited Partners Association introduced a reporting template for investors to use to report comprehensive data related to private equity fees; this form, which is being adopted by a number of U.S. pension plans, could also serve as a template for fee reporting for hedge fund and co-mingled real assets fees. Other funds have taken steps to increase transparency and disclosure around all alternative investment fees:

- The Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island in recent years has put in place an extremely robust fee-reporting mechanism that makes not only complete management and performance fee data publicly available, but also the fee terms in each contract by manager.

- In 2015, the New York City comptroller announced that all investment managers, including hedge funds and private equity firms, would have to fully disclose all fees as a stipulation of doing business with the city.[80]

- The New Jersey Pension Fund announced in 2015 that it would disclose five years’ worth of fee data on all of its investments.[81]

Notably, in addition to taking steps to increase transparency around fees, all three of these pension funds also made significant reductions to their hedge fund programs soon afterward, which suggests that quantifying and disclosing fees leads investors to reconsider these expensive investments. Ashby Monk and Rajiv Sharma of Stanford University’s Global Projects Center explore this phenomenon in detail in their paper “Organic Finance,” which compares the finance sector with the food industry:

“The increasing complexity and de-localization of finance has allowed for an obfuscation of fees and costs. … [We] draw parallels to the food industry, which has also seen a revolt against complex and de-localized food products. As people begin to understand the ingredients in their food, and the consequences for their own health, they consume food products differently, often preferring organic foods. Similarly, as investors begin to understand the fees and costs in their investment products, and the consequences for their and the capitalist system’s health, they are beginning to invest differently, preferring efficient and transparent products rooted in the real economy.”[82]

Alternative investment managers have vehemently opposed these efforts to increase fee transparency. Attempts to pass legislation requiring fee transparency have foundered in states like Alabama, Kentucky and New Jersey, with stiff opposition from industry lobbying groups such as the American Investment Council, although fee transparency legislation is currently moving in Illinois, [83] and will likely be introduced elsewhere in the next several years.

Pension funds foregoing alternatives altogether

Although most pension funds have invested in alternatives in attempts to achieve their assumed rates of return, there are some public pension funds that do not invest in alternatives or any type of actively managed investments. For example, the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Nevada is overseen by one asset manager and only invests in a passive, traditional mix of investments, and yet consistently posts better returns than its peers,[84] even beating the much-admired Harvard endowment by a significant margin over the last10 years.[85]

In April 2017, North Carolina State Treasurer Dale Folwell announced that the state pension fund would begin the process of divesting from all alternative investments. Explaining his decision to withdraw from alternatives in favor of inexpensive, internally managed indexed funds, Folwell stated, “It’s not emotional. It’s not political. It’s mathematical.…We don’t own alternative investments. They own us. I think they increase complexity and reduce value.”[86]

For many public pension fund trustees, increasing funding ratios in order to meet future liabilities is a top concern—and this is particularly pressing for trustees in states facing budget or pension crises. Our analysis demonstrates that cutting fees to alternative asset managers in half, from an estimated 1.8 and 18 percent to 0.9 and 9 percent, saves the average pension fund $317 million in fees per year; when compounded over five-, 15- and 30-year periods, these savings add up, respectively, to $1.8 billion, $8 billion, and $30 billion for each pension plan.

As trustees, states and taxpayers weigh options for addressing funding shortfalls, lowering fees on alternative investments should be at the forefront. To achieve this, we recommend that public pension funds currently invested in alternatives take the following steps:

- Disinvestment and reallocation. Immediately begin the process of divesting from fund of funds, which represent the most costly type of alternative investment due to the additional layer of fees charged to the investor.

- Adopt policies requiring full accounting, management and disclosure of all fees by alternative investment managers, including management fees, performance fees and all other fees, to improve fee management. Fee disclosure should be provided from the inception of each alternative investment, and should be made publicly available. Pension funds should also require that all alternatives managers provide annual financial statements that include operating expenses.

- Fee limits. Adopt specific policies with respect to acceptable fee limits, with fees not to exceed 0.9 percent for management and 9 percent for performance. We encourage pension funds to consider lowering fees even further, exploring or developing alternative fee structures, along with hurdle rates and high water marks that ensure the pension fund is sufficiently compensated for the risks it takes as an investor in alternatives.

- Fee compilation. Support the development of a nonprofit organization to which pension funds can report all fees paid to investment managers and fee terms by investment manager, to promote market efficiency in the asset management industry and correct the asymmetry of information and misaligned incentives between pension funds and alternatives managers. The nonprofit organization would make this data publicly available without naming each pension fund. Such an arrangement would essentially promote collective bargaining power for public pension funds on fees charged.

- Develop and support legislative policies that require annual public disclosure of all fees by fund and by asset manager, and that place a cap on fees paid to asset managers in order to ensure that taxpayers are not shouldering a disproportionate burden of the costs of fully funding retirement security for working Americans and that Wall Street pays its fair share.

These recommendations address the problems with current exorbitant fee structures commonplace among alternative investments: (1) high management fees create an unequal sharing of risk and return, such that pension funds assume all of the risk and only some of the reward, which leads to (2) a dangerous misalignment of incentives where managers profit based principally on the size of their assets under management, not on the performance of those assets. The root cause of these problems is a profound lack of transparency on fee structures.

Investment management firms are likely to oppose these recommendations. However, pension funds aiming to reverse the transfer of wealth from taxpayers and workers to Wall Street can and should work together to demand lower fees from the alternative investment industry; we believe these recommendations mark a clear path toward achieving this.

Appendix: Methodology

We analyzed a set of 12 public pension funds, with a total of $787 billion in assets under management (AUM) and $182 billion in alternative AUM as of the most recent fiscal year reported. Total alternative investments for these pension funds as of the most recent fiscal year reported are as follows:

- Hedge fund AUM: $59 billion

- Private equity AUM: $84 billion

- Co-mingled real assets AUM: $39 billion

The following table lists average and median AUM for the pension funds in our study:

| Average | Median | |

| Hedge fund AUM | $4.9 billion | $4.1 billion |

| Private equity AUM | $6.9 billion | $6.3 billion |

| Co-mingled real assets AUM | $3.2 billion | $1.6 billion |

| Total AUM | $65.6 billion | $53.9 billion |

Alternative investment managers and consultants typically fail to disclose all information related to the fees they charge to pension funds. When they do disclose these fees, the figures are often unreliable, either because they fail to account for all fees (management, performance or “carry,” pass-through and others), or because the terms of the investment contracts preclude pension funds from having the right to know about these fees in the first place.[87]

With the exception of the Employees Retirement System of Rhode Island, which appears to report relatively complete fee data for all alternative investments, and New York Common, which reports complete fee data for its hedge fund investments, the majority of the pension funds in our study do not disclose enough information on fees paid on alternative investments. Therefore, this analysis uses the following methodology to estimate these costs:

- Gross alternative investment returns are calculated by investment type using the following assumptions:

- Management fees are calculated conservatively at 1.8 percent of AUM.

- Incentive fees are calculated conservatively at 18 percent of gross return less management fees.

- Performance fees were adjusted to $0 for fiscal years where net returns for hedge funds were negative.

- To account for the fact that some alternative investment contracts include hurdle rate provisions, we included the following hurdle rates on gross returns, based on the most recent Preqin data on average hurdle rates by investment type:

- For compounded savings projections, we used an assumed rate of return of 7 percent. This is a conservative assumption, based on the average assumed rate of return among U.S. state and local pension funds of 7.52 percent,[91] in recognition of the national trend of public pension funds lowering their assumed rates of return. We based these projections on the average estimated alternatives fees paid over the last five years, divided in half, which we used to determine savings in year one.

Sample selection

Beginning with a list of the 80 largest U.S. state public pension funds in terms of AUM with investments in alternatives (which included some New York City and Los Angeles pension funds due to their comparable size to state public pension funds), we selected the pension funds included in this report based on the following factors:

- Amount and duration of alternatives investment. We selected public pension funds that have consistently invested in hedge funds, private equity and real estate for at least the last five years.

- Availability of data. We first identified those pension funds that report complete fee data for alternative investments, including management and performance fees. We then identified those funds that report reliable AUM and net return data for all alternative investments. Finally, we included those funds that do not make these data publicly available, but did respond to a public records request.

- State budget and pension funding context. We selected pension funds from states facing budget crises and/or pension funding crises, as determined by recent state legislation (introduced or proposed) attempting to address either issue.

This selection process resulted in a set of 12 public pension funds for which we had sufficient data to conduct a fees analysis of alternative investments.

Limitations

- Availability of data. Our analysis was limited principally by availability of data. Because many pension funds do not make alternative investment AUM and net return data clear and easily accessible to the public, we had to submit public records requests to obtain data from many of the public pension funds we hoped to review. Timeliness and adequacy of responses we received varied widely, so we were able to include only those funds for which we had data. Thus, we had to omit a number of public pension funds from our sample.

- Our sample is also biased toward East Coast and Central U.S. pension funds, partially because these funds are the most likely to be facing public budget and pension funding crises.

- Co-mingled real assets data. While most pension funds in our sample identified several categories of real assets investments that allowed us to determine which categories were most likely the type of real assets that use the alternative fee structure, in some cases we had to rely on limited descriptions of these investments to identify alternative real assets.

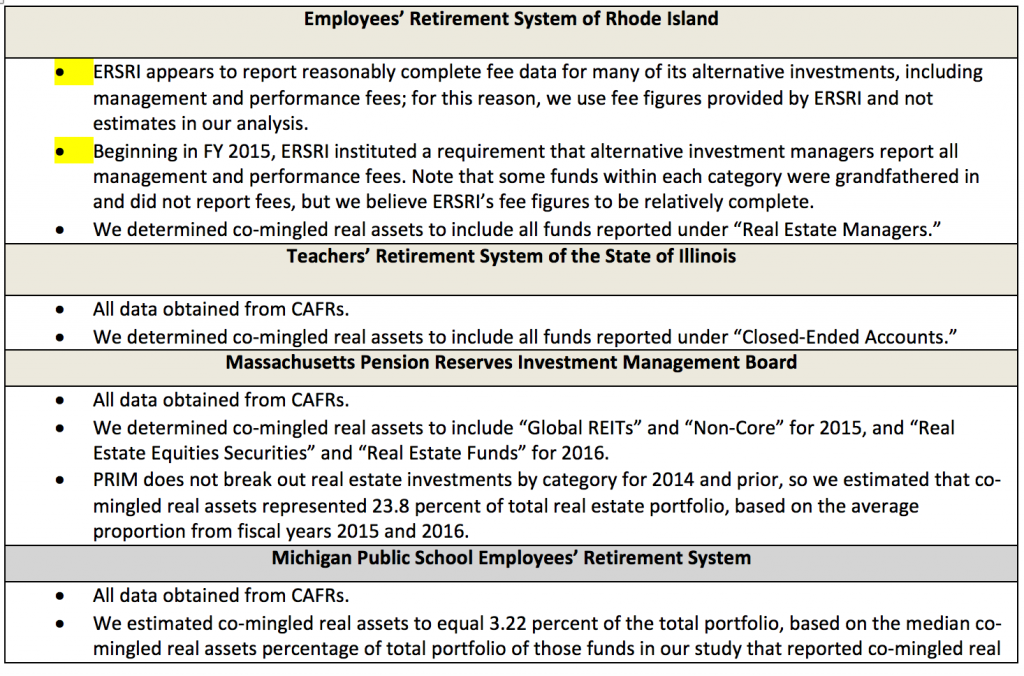

Additional notes on specific funds:

We obtained AUM and net return data for each pension fund’s alternative and total fund investments from the following sources: comprehensive annual financial reports (CAFRs) for the pension funds, investment reports, websites and/or public records requests. The following table provides more detailed information on data sources for each fund:

| ERSRI appears to report reasonably complete fee data for many of its alternative investments, including management and performance fees; for this reason, we use fee figures provided by ERSRI and not estimates in our analysis. |

| · Beginning in FY 2015, ERSRI instituted a requirement that alternative investment managers report all management and performance fees. Note that some funds within each category were grandfathered in and did not report fees, but we believe ERSRI’s fee figures to be relatively complete.

· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all funds reported under “Real Estate Managers.” |

| Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois |

| · All data obtained from CAFRs.

· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all funds reported under “Closed-Ended Accounts.” |

| Massachusetts Pension Reserves Investment Management Board |

| · All data obtained from CAFRs.

· We determined co-mingled real assets to include “Global REITs” and “Non-Core” for 2015, and “Real Estate Equities Securities” and “Real Estate Funds” for 2016. · PRIM does not break out real estate investments by category for 2014 and prior, so we estimated that co-mingled real assets represented 23.8 percent of total real estate portfolio, based on the average proportion from fiscal years 2015 and 2016. |

| Michigan Public School Employees’ Retirement System |

| · All data obtained from CAFRs.

· We estimated co-mingled real assets to equal 3.22 percent of the total portfolio, based on the median co-mingled real assets percentage of total portfolio of those funds in our study that reported co-mingled real assets clearly. |

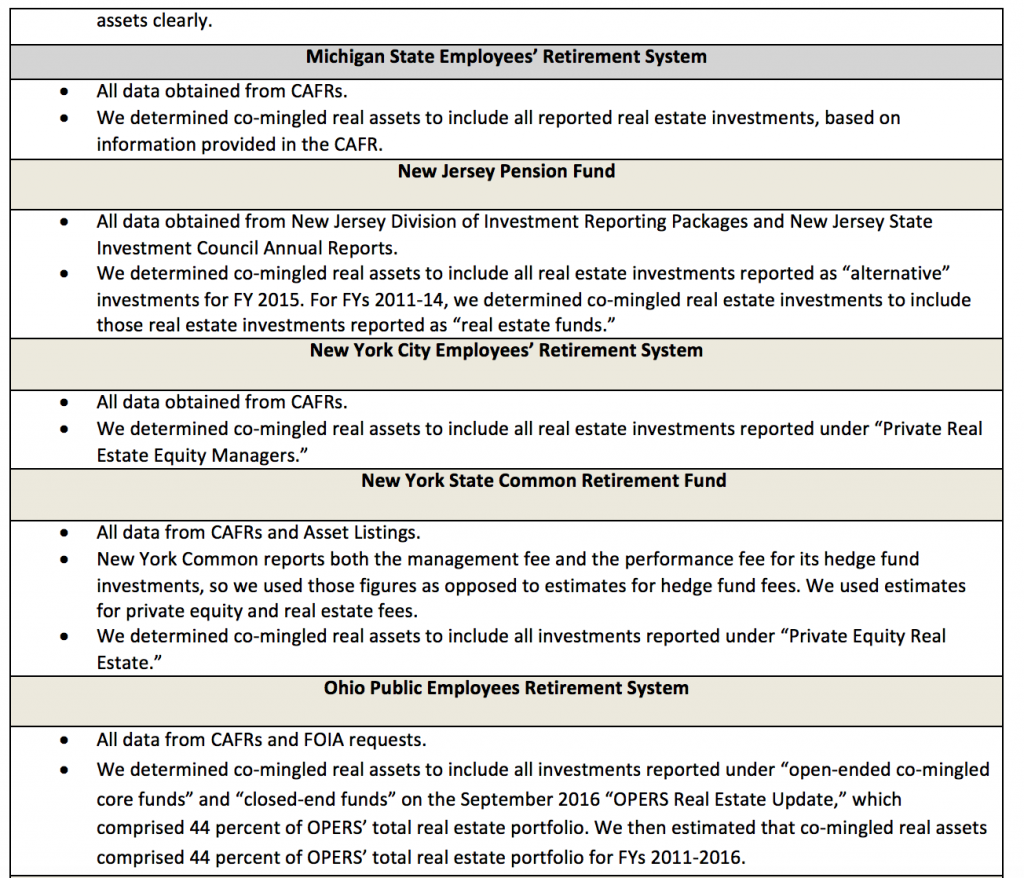

| Michigan State Employees’ Retirement System |

| · All data obtained from CAFRs.

· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all reported real estate investments, based on information provided in the CAFR. |

| New Jersey Pension Fund |

| · All data obtained from New Jersey Division of Investment Reporting Packages and New Jersey State Investment Council Annual Reports.

· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all real estate investments reported as “alternative” investments for FY 2015. For FYs 2011-14, we determined co-mingled real estate investments to include those real estate investments reported as “real estate funds.” |

| New York City Employees’ Retirement System |

· All data obtained from CAFRs.· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all real estate investments reported under “Private Real Estate Equity Managers.” |

New York State Common Retirement Fund |

· All data from CAFRs and Asset Listings.· New York Common reports both the management fee and the performance fee for its hedge fund investments, so we used those figures as opposed to estimates for hedge fund fees. We used estimates for private equity and real estate fees.· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all investments reported under “Private Equity Real Estate.” |

Ohio Public Employees Retirement System |

· All data from CAFRs and FOIA requests.· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all investments reported under “open-ended co-mingled core funds” and “closed-end funds” on the September 2016 “OPERS Real Estate Update,” which comprised 44 percent of OPERS’ total real estate portfolio. We then estimated that co-mingled real assets comprised 44 percent of OPERS’ total real estate portfolio for FYs 2011-2016. |

Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System |

· All data obtained from CAFRs.· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all real estate investments described as “Limited Partnerships.” |

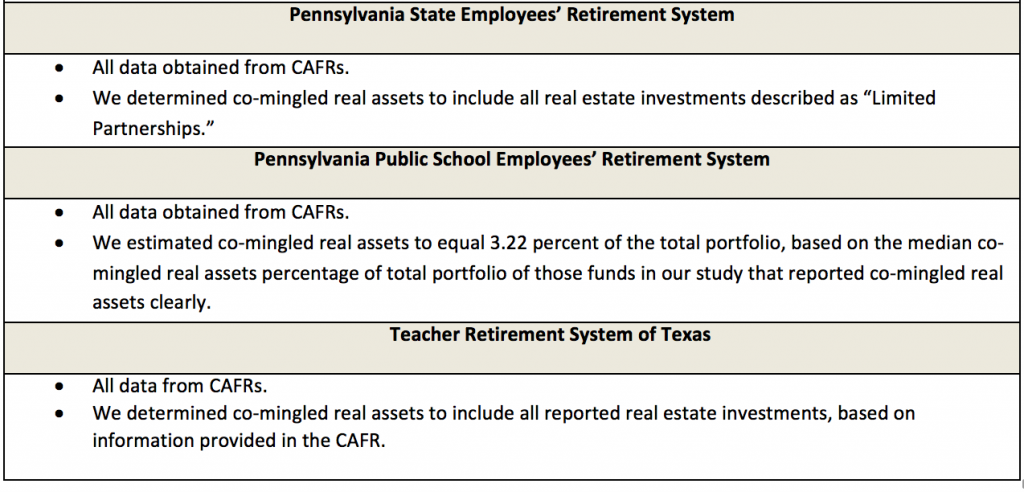

Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System |

· All data obtained from CAFRs.· We estimated co-mingled real assets to equal 3.22 percent of the total portfolio, based on the median co-mingled real assets percentage of total portfolio of those funds in our study that reported co-mingled real assets clearly. |

Teacher Retirement System of Texas |

· All data from CAFRs.· We determined co-mingled real assets to include all reported real estate investments, based on information provided in the CAFR. |

In addition to divesting from hedge funds altogether or reducing fees, another way to address exorbitant alternatives fees is by reducing the number of external managers used by the pension fund—a process CalPERS began in 2015 when it announced that it was cutting its number of external managers.

In 2016, the Institutional Limited Partners Association introduced a reporting template for investors to use to report comprehensive data related to private equity fees; this form, which is being adopted by a number of U.S. pension plans, could also serve as a template for fee reporting for hedge fund and co-mingled real assets fees. Other funds have taken steps to increase transparency and disclosure around all alternative investment fees:

- The Employees’ Retirement System of Rhode Island in recent years has put in place an extremely robust fee-reporting mechanism that makes not only complete management and performance fee data publicly available, but also the fee terms in each contract by manager.

- In 2015, the New York City comptroller announced that all investment managers, including hedge funds and private equity firms, would have to fully disclose all fees as a stipulation of doing business with the city.[80]

- The New Jersey Pension Fund announced in 2015 that it would disclose five years’ worth of fee data on all of its investments.[81]

Notably, in addition to taking steps to increase transparency around fees, all three of these pension funds also made significant reductions to their hedge fund programs soon afterward, which suggests that quantifying and disclosing fees leads investors to reconsider these expensive investments. Ashby Monk and Rajiv Sharma of Stanford University’s Global Projects Center explore this phenomenon in detail in their paper “Organic Finance,” which compares the finance sector with the food industry:

“The increasing complexity and de-localization of finance has allowed for an obfuscation of fees and costs. … [We] draw parallels to the food industry, which has also seen a revolt against complex and de-localized food products. As people begin to understand the ingredients in their food, and the consequences for their own health, they consume food products differently, often preferring organic foods. Similarly, as investors begin to understand the fees and costs in their investment products, and the consequences for their and the capitalist system’s health, they are beginning to invest differently, preferring efficient and transparent products rooted in the real economy.”[82]

Alternative investment managers have vehemently opposed these efforts to increase fee transparency. Attempts to pass legislation requiring fee transparency have foundered in states like Alabama, Kentucky and New Jersey, with stiff opposition from industry lobbying groups such as the American Investment Council, although fee transparency legislation is currently moving in Illinois, [83] and will likely be introduced elsewhere in the next several years.

Pension funds foregoing alternatives altogether

Although most pension funds have invested in alternatives in attempts to achieve their assumed rates of return, there are some public pension funds that do not invest in alternatives or any type of actively managed investments. For example, the Public Employees’ Retirement System of Nevada is overseen by one asset manager and only invests in a passive, traditional mix of investments, and yet consistently posts better returns than its peers,[84] even beating the much-admired Harvard endowment by a significant margin over the last10 years.[85]

In April 2017, North Carolina State Treasurer Dale Folwell announced that the state pension fund would begin the process of divesting from all alternative investments. Explaining his decision to withdraw from alternatives in favor of inexpensive, internally managed indexed funds, Folwell stated, “It’s not emotional. It’s not political. It’s mathematical.…We don’t own alternative investments. They own us. I think they increase complexity and reduce value.”[86]

For many public pension fund trustees, increasing funding ratios in order to meet future liabilities is a top concern—and this is particularly pressing for trustees in states facing budget or pension crises. Our analysis demonstrates that cutting fees to alternative asset managers in half, from an estimated 1.8 and 18 percent to 0.9 and 9 percent, saves the average pension fund $317 million in fees per year; when compounded over five-, 15- and 30-year periods, these savings add up, respectively, to $1.8 billion, $8 billion, and $30 billion for each pension plan.

As trustees, states and taxpayers weigh options for addressing funding shortfalls, lowering fees on alternative investments should be at the forefront. To achieve this, we recommend that public pension funds currently invested in alternatives take the following steps:

- Disinvestment and reallocation. Immediately begin the process of divesting from fund of funds, which represent the most costly type of alternative investment due to the additional layer of fees charged to the investor.

- Adopt policies requiring full accounting, management and disclosure of all fees by alternative investment managers, including management fees, performance fees and all other fees, to improve fee management. Fee disclosure should be provided from the inception of each alternative investment, and should be made publicly available. Pension funds should also require that all alternatives managers provide annual financial statements that include operating expenses.

- Fee limits. Adopt specific policies with respect to acceptable fee limits, with fees not to exceed 0.9 percent for management and 9 percent for performance. We encourage pension funds to consider lowering fees even further, exploring or developing alternative fee structures, along with hurdle rates and high water marks that ensure the pension fund is sufficiently compensated for the risks it takes as an investor in alternatives.

- Fee compilation. Support the development of a nonprofit organization to which pension funds can report all fees paid to investment managers and fee terms by investment manager, to promote market efficiency in the asset management industry and correct the asymmetry of information and misaligned incentives between pension funds and alternatives managers. The nonprofit organization would make this data publicly available without naming each pension fund. Such an arrangement would essentially promote collective bargaining power for public pension funds on fees charged.

- Develop and support legislative policies that require annual public disclosure of all fees by fund and by asset manager, and that place a cap on fees paid to asset managers in order to ensure that taxpayers are not shouldering a disproportionate burden of the costs of fully funding retirement security for working Americans and that Wall Street pays its fair share.

These recommendations address the problems with current exorbitant fee structures commonplace among alternative investments: (1) high management fees create an unequal sharing of risk and return, such that pension funds assume all of the risk and only some of the reward, which leads to (2) a dangerous misalignment of incentives where managers profit based principally on the size of their assets under management, not on the performance of those assets. The root cause of these problems is a profound lack of transparency on fee structures.

Investment management firms are likely to oppose these recommendations. However, pension funds aiming to reverse the transfer of wealth from taxpayers and workers to Wall Street can and should work together to demand lower fees from the alternative investment industry; we believe these recommendations mark a clear path toward achieving this.

Appendix: Methodology

We analyzed a set of 12 public pension funds, with a total of $787 billion in assets under management (AUM) and $182 billion in alternative AUM as of the most recent fiscal year reported. Total alternative investments for these pension funds as of the most recent fiscal year reported are as follows:

- Hedge fund AUM: $59 billion

- Private equity AUM: $84 billion

- Co-mingled real assets AUM: $39 billion

The following table lists average and median AUM for the pension funds in our study:

| Average | Median | |

| Hedge fund AUM | $4.9 billion | $4.1 billion |

| Private equity AUM | $6.9 billion | $6.3 billion |

| Co-mingled real assets AUM | $3.2 billion | $1.6 billion |

| Total AUM | $65.6 billion | $53.9 billion |

Alternative investment managers and consultants typically fail to disclose all information related to the fees they charge to pension funds. When they do disclose these fees, the figures are often unreliable, either because they fail to account for all fees (management, performance or “carry,” pass-through and others), or because the terms of the investment contracts preclude pension funds from having the right to know about these fees in the first place.[87]

With the exception of the Employees Retirement System of Rhode Island, which appears to report relatively complete fee data for all alternative investments, and New York Common, which reports complete fee data for its hedge fund investments, the majority of the pension funds in our study do not disclose enough information on fees paid on alternative investments. Therefore, this analysis uses the following methodology to estimate these costs:

- Gross alternative investment returns are calculated by investment type using the following assumptions:

- Management fees are calculated conservatively at 1.8 percent of AUM.

- Incentive fees are calculated conservatively at 18 percent of gross return less management fees.

- Performance fees were adjusted to $0 for fiscal years where net returns for hedge funds were negative.

- To account for the fact that some alternative investment contracts include hurdle rate provisions, we included the following hurdle rates on gross returns, based on the most recent Preqin data on average hurdle rates by investment type:

- For compounded savings projections, we used an assumed rate of return of 7 percent. This is a conservative assumption, based on the average assumed rate of return among U.S. state and local pension funds of 7.52 percent,[91] in recognition of the national trend of public pension funds lowering their assumed rates of return. We based these projections on the average estimated alternatives fees paid over the last five years, divided in half, which we used to determine savings in year one.

Sample selection